Editors: Tom Whipple, Steve Andrews

Quote of the Week

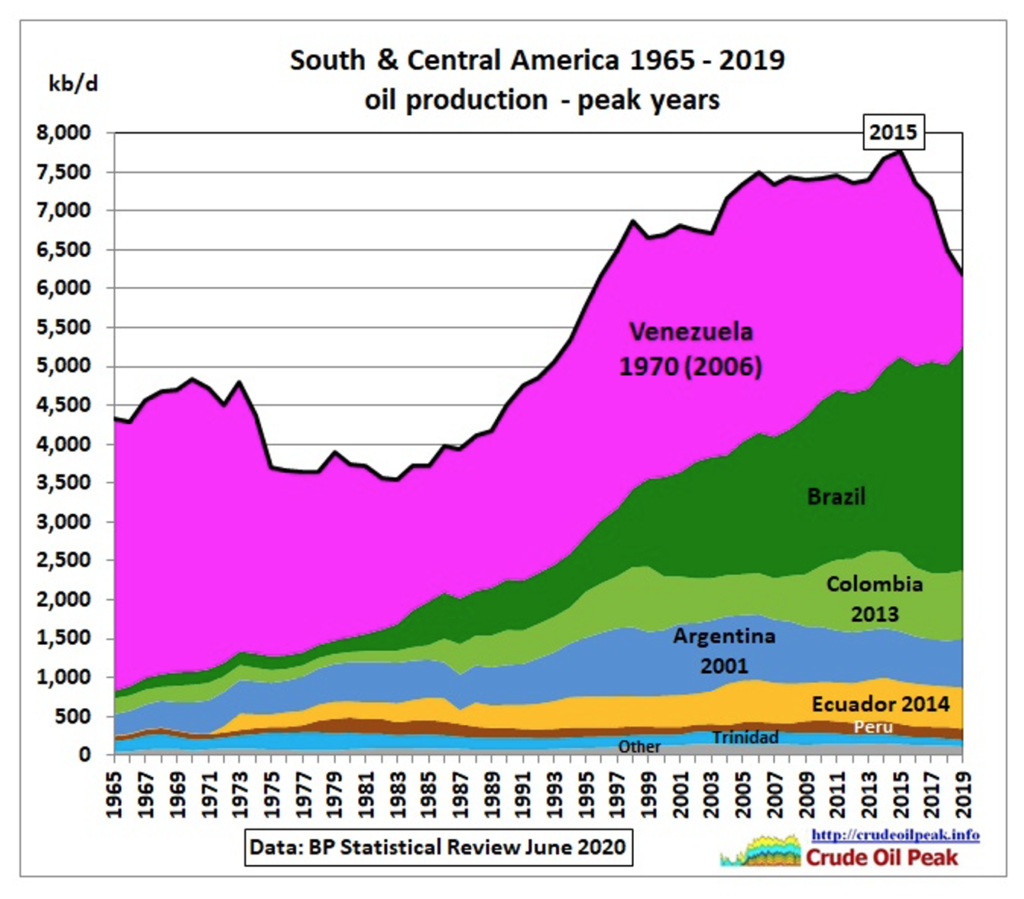

“[South America’s oil] production peaked in 2015 due to Venezuela’s production collapse. Brazil’s production has not yet peaked but is unlikely to offset Venezuela’s decline. All other countries together are on a bumpy production plateau for the last 20 years.”

Matt Mushalik, Australian engineer and oil industry commentator

Graphic of the Week

| Contents 1. Energy prices and production 2. Geopolitical instability 3. Climate change 4. The global economy and the coronavirus 5. Renewables and new technologies 6. Briefs |

1. Energy prices and production

Oil: Crude futures rode a late session upswing to end 2020 higher, as the market looked to a Jan. 4th OPEC+ meeting for direction. WTI settled at $48.52, and Brent settled at $51.80. With oil markets closed on Jan. 1st for the New Year’s Day holiday, the next driver will likely be the OPEC+ group meeting when ministers will decide on production quotas for February. Russian Deputy Prime Minister Novak floated the possibility of another 500,000 b/d increase for February, the maximum monthly amount allowed under the rules. Global crude oil markets lost about a fifth of their value in 2020 as coronavirus lockdowns paralyzed much of the worldwide economy.

Crude oil comes in dozens of varieties that differ by density and sulfur content. WTI, Brent, and Dubai act as reference points against which other grades are priced. They also are the basis for financial contracts that allow players in the oil market to hedge against and speculate on price swings. Benchmark prices are determined either on futures exchanges or by price-reporting agencies such as S&P Global Platts and Argus Media. Gaps between prices for WTI, Brent, and Dubai send signals to traders about demand in different regions or for crude with specific characteristics, encouraging oil to flow where it is most in need.

Last year benchmarks and methodologies were tested, WTI endured the sternest test. The problem stemmed from Cushing, Okla., the primary commercial storage location for US oil. Anyone holding CME’s futures contracts when they expire has to take ownership of oil at the hub. That means the contracts’ price typically converges with oil prices at Cushing in the run-up to their last day of trading.

As the May contracts came close to expiration in the spring, rapidly filling storage space in Cushing left traders reluctant or unable to accept the oil delivery. That sent some WTI futures prices careening on Apr. 20th. By the end of the day, futures settled at minus $37.63 a barrel, a precipitous decline whose causes are still disputed. It was a seminal moment in the market’s history. It also showed that the influence of local conditions at Cushing makes WTI an unsuitable benchmark.

Prices have somewhat recovered. But those jarring moves of the spring added urgency to arguments about whether benchmarks used since the 1980s adequately reflect the modern oil market. Newer gauges, including Shanghai-traded futures and a contract for Abu Dhabi’s Murban crude that will make its debut in March, are expected to grow in popularity.

The crash rippled through the physical market, where, for example, Saudi Arabia sets prices for exports to the US using an assessment tied to futures prices.

The emergence of the US as an oil-exporter in recent years, combined with rapid growth in Asian demand and sliding production in Europe, has transformed crude flows worldwide while the pricing system based on three benchmark crudes—West Texas Intermediate in the US, Brent in Europe, and Dubai in the Middle East—has broadly stayed the same.

OPEC: The cartel and its allies will likely have a busy year. At the top of the list will be shepherding oil prices gradually higher to ease their budget pain and reclaiming market share as oil demand returns, while avoiding a supply squeeze that would upend the global economy. The goals are not that much different from the previous four years of OPEC+ cooperation. However, the ministers have also resolved to meet every month in an attempt to remain nimble in the face of the pandemic.

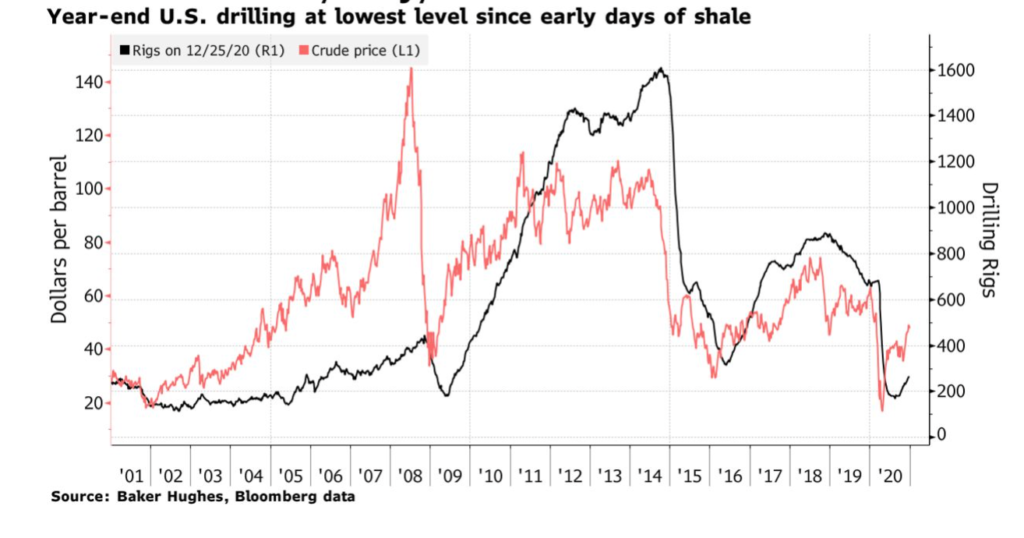

Shale Oil: The crisis that enveloped the oil industry in 2020 can be measured in various ways, but in the US there may be no better single gauge than the tally of drilling rigs in operation. The weekly data shows, at a glance, the level of confidence from hundreds of companies that drill shale wells from Texas to North Dakota. As the price of crude plunged amid the pandemic, those operators slashed spending and cut drilling crews.

The result was a rig count that collapsed to levels not seen since the advent of the shale era 15 years ago, as crude demand and prices plunged. And while the rig count has rebounded since August, both prices and active rigs remain far below where they began in 2020. Next year isn’t expected to get much better with US oil prices widely expected to be stranded between $40 and $50 a barrel, forcing explorers to make hard choices about whether new drilling is worth it.

The slump reflects a massive readjustment for the US oil industry. Having ridden to a position of global preeminence on the back of the shale boom, the US reemerged as a significant exporter rivaling Saudi Arabia and Russia. Still, the pandemic hit hard and forced producers to make painful cost cuts. Domestic output is ending the year steady but about 16 percent, or 2.1 million barrels a day, below its pre-pandemic peak, a level where it’s widely expected to stay, absent a dramatic price spike. In the meantime, OPEC has managed to regain its former position as the dominant player globally.

The price crash triggered by the pandemic has been brutal for the oil industry across the US, but nowhere more so than North Dakota. Here, the Bakken’s explosive growth — the first significant oilfield to emerge during the shale revolution — has placed the sector at the heart of the state’s economy. As North Dakota emerges from the downturn, the oil industry’s prospects seem far less certain. Investment has dried up, political support is waning, and the future of a critical pipeline transporting crude from the state hangs in the balance.

North Dakota entered 2020 at record production levels. Output was second only to Texas as it pumped out almost 1.5 million barrels of oil a day, or 12 percent of the nation’s total. “March changed everything,” said Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota department of mineral resources. The crash sent North Dakota oil production to a seven-year low. North Dakota operators shut almost a quarter of their wells, four in five rigs were laid down, and output slid 40 percent. By most metrics, said Helms, “the numbers for 2020 are the worst they have ever been.”

Natural Gas: A sharp rise in global prices is proving a relief for companies seeking to export more fuel from the US after a year of setbacks from coronavirus and glutted supply. Liquefied natural gas delivered into East Asia surged above $10 per million British thermal units in Asia this month on the back of cold weather and supply interruptions. The rally spilled into Europe, with gas in the UK selling for a third more than a year ago.

The prices are well above markets in the US, improving the economics of exporting American gas. Shares of Cheniere Energy, the largest US LNG exporter have outpaced the past month’s stock market. While most of the company’s sales are committed under long-term contracts, the Houston-based company “is able to capitalize on higher spot LNG prices” by selling uncontracted volumes through its trading arm, Cheniere Marketing.

US LNG feedgas demand surged Dec. 28th to near a record set two weeks earlier as spot prices for deliveries to Northeast Asia, the world’s biggest import market, rose to the highest level in six years. The activity comes despite long wait times at the Panama Canal for LNG tankers arriving without a reservation. Heading into 2021, US producers are being buoyed by strong market fundamentals. Peak demand and pockets of supply tightness have been bullish for prices, while high tanker charter rates have not deterred robust exports from the Gulf and Atlantic coasts.

LNG traders anticipate a swift demand recovery in 2021 after a year in which the coronavirus pandemic prompted dramatic price swings. Colder weather in key importing nations, outages at significant production hubs, and congestion along global shipping routes have already combined to push Asia’s spot prices to the highest level since 2014. That’s a more than sixfold jump from a record low in April, making Asian LNG the best performer among major commodities in 2020.

Due to industry concerns over possible tighter permitting to drill on federal and Native American land under a Biden Administration, most significant producers have stocked federal permits over the last 12 months or shifted much of their drilling activity plans to state and private lands. Despite the Trump Administration’s efforts to encourage more energy production on federal leases, there has only been modest oil and gas growth over the past few years.

Prognosis: Average oil demand will probably rise by the most on record in 2021. The International Energy Agency projects consumption will increase by almost 6 million b/d this year but will average just 96.9 million b/d — still well below the pre-pandemic record of 100 million in 2019. Oil demand was also forecast initially to expand by about 1 million b/d in 2020 and 2021. That means consumption in 2021 should be at least 5 million b/d below where it would have been without the coronavirus.

The sector with significantly lower demand this year will likely be jet fuel, with airlines consuming 2.5 million b/d less than before the pandemic. According to the IEA, gasoline and diesel demand are expected to be restricted in the first half of the year until vaccines are more widely available and will only reach 97-99 percent of pre-pandemic levels. A drop in economic output will also hurt demand with reduced manufacturing and fewer goods shipped by sea.

The outlook for oil supply is more complicated. Investment in the industry has been falling, and the pandemic has delayed drilling programs. US shale, which transformed the oil and gas industry for much of the past five years, is in trouble. According to the EIA, this relatively expensive source of supply has been hard hit by the crash in prices, with US crude output falling from a record 12.3 million b/d in 2019 to 11.3 million in 2020. Shale oil production stabilized in the second half of 2020, but the days of rapid growth are behind it for now. The EIA sees US supply slipping to 11.1m b/d in 2021.

One of the critical variables for oil will be how shale and other producers respond if prices rise much above $50 a barrel — a level where most companies can cover their costs. Globally, the IEA sees non-OPEC growing by 500,000 b/d this year after falling 2.6 million b/d in 2020.

The supply surplus that developed due to the pandemic puts a lot of weight on what OPEC+ will do. The alliance called off a month-long price war in April and agreed to cut almost 10 percent of global oil production to rescue the market. The deal was meant to taper, allowing countries to produce more as demand recovers. But a drawn-out crisis has left them stuck with more than 7 million b/d of crude still offline. They are expected to meet again on Jan. 4th to discuss adding back 500,000 b/d.

The most significant geopolitical shift in 2021 will probably be the election of Joe Biden as US president. President Trump became heavily involved with OPEC decisions, pressuring Saudi Arabia to raise or lower production in return for his support. President-elect Joe Biden is expected to be less hands-on with the cartel, but he may end up being no less influential. The potential revival of the Iran nuclear deal could result in Tehran adding close to 2 million b/d of crude back to the market if US sanctions ease.

2. Geopolitical instability

(These are the situations that reduce the world’s energy supplies or have the potential to do so.)

Iran: Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif on Thursday accused President Trump of attempting to fabricate a pretext to attack Iran and said Tehran would defend itself forcefully. In recent days there has been increased concern and vigilance about what Iranian-backed forces might do in the lead up to the anniversary of the Jan. 3rd US drone strike in Iraq that killed top Iranian general Soleimani, the official said. Washington blames Iran-backed militia for regular rocket attacks on US facilities in Iraq, including near the embassy. No known Iran-backed groups have claimed responsibility.

The US flew two nuclear-capable B-52 bombers to the Middle East in a message of deterrence to Iran on Wednesday, but the bombers have since left the region. The Pentagon has decided to keep the aircraft carrier Nimitz in the Middle East, a weeklong muscle-flexing strategy to deter Iran from attacking American troops and diplomats in the Persian Gulf.

Iraq: Tehran has slashed the amount of natural gas it exports to Iraq and threatened further cutbacks over unpaid bills, increasing the likelihood of more electricity shortages. Iraq has received 5 million cubic meters a day since Iran cut its daily exports from 50 million cubic meters two weeks ago. The Iranian government told Iraq it would reduce its supplies to 3 million cubic meters a day starting Sunday but has not yet implemented the move. Iran began to cut exports to its neighbor after Iraq fell behind on its gas payments. Iraq owes around $2.7 billion in unpaid bills.

Along with Iraq’s reiterated target for crude oil production of 7 million b/d by 2025, from the previous 5 million b/d, Baghdad has also said it will stop flaring gas by the same point (and to halt importing fuel from Iran by 2025 as well). These moves would be in line with Iraq’s endorsement in May 2017 of the United Nations and World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring initiative to end routine flaring by 2030. Since making the commitment to reducing gas flaring nearly three years ago, little of real significance has yet been achieved.

An oil tanker off the coast of Iraq discovered an object attached to its hull, the latest incident highlighting the risk to ships in the waters near the Arabian Peninsula. According to a statement from the owner, the Liberia-flagged Pola noticed a “suspicious object” as it was discharging cargo onto another vessel.

The object was later found to be a bomb, and an Iraqi naval force with an explosives team was sent to defuse the device. It was not immediately clear who may have placed it on the tanker. The Pola, a Suezmax-class vessel, has been anchored since Nov. 7th and is likely being used as floating storage for oil. When the object was discovered, the tanker appeared to be transferring cargo to the Nordic Freedom, owned by Nordic American Tankers Ltd. According to an official, the Pola buys oil offshore and isn’t affiliated with Iraq’s export terminals.

Baghdad plans to boost the capacity of its southern oil export facilities by 72 percent to 6 million b/d after 2023 and wants to build storage tanks to help reach that target. Iraq will construct 24 storage tanks with a capacity of 58,000 cubic meters to help ramp up its southern export capacity from 3.5 million b/d now. Iraq pumped 3.8 million b/d during November, in line with its 3.804 million b/d quota.

Venezuela: Exports plummeted this month as US sanctions have left some of the South American country’s cargoes stranded in Asia, and competition with fellow OPEC+ members is set to heat up. A linchpin of the Venezuelan economy, oil sales slumped by about half from November to 232,000 b/d, according to shipping reports and vessel-tracking data compiled by Bloomberg. That leaves exports for the year at their lowest in about seven decades. Cargoes that load in December could arrive in Asia as early as January, just as the OPEC and its allies might increase supplies further in February on Jan. 4th.

Yemen: An attack on an airport in Yemen killed at least 22 and wounded more than 50 people moments after the country’s newly sworn-in cabinet arrived. Sounds of explosions followed by gunfire shook the city of Aden’s airport. The blasts took place moments after cabinet ministers from a government-backed by Saudi Arabia had landed from Riyadh. The government’s information minister said all the members of the cabinet were safe following the attack.

The violence presents a challenge to the new government sworn in on Dec. 26th as part of a power-sharing agreement brokered by Saudi Arabia to end fighting between loyalists of the country’s president and southern separatists. They are allied with the United Arab Emirates. No one claimed responsibility for the attack, but Western officials and analysts said it was likely carried out by the Houthis, who receive military backing from Iran. The Western officials didn’t rule out the possibility that al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula or disgruntled factions within the southern separatist camp could have been responsible.

3. Climate change

We may remember 2020 as the year the world started to reverse centuries of damage to the climate. Before the start of the year, the European Commission announced a new Green Deal, which would become the centerpiece of the European Union’s economic recovery plan. Several more of the largest global economies—including China, responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than any other country—also came out with net-zero pledges. As oil and gas prices plunged due to the pandemic, NextEra Energy Inc., the world’s largest wind power supplier, overtook Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp as the world’s most valuable energy company. And in November, the US voted to make Joe Biden, who adopted climate change as one of his signature campaign issues, its next president.

Fires were terrible last year—particularly in northern California. But we also experienced an unprecedented Atlantic hurricane season, and it was hotter than it’s ever been in some places. Phoenix set triple-digit heat records, and Siberia hit 100 degrees. There was a record number of climate disasters that each cost $1 billion or more. Climate migration had already begun, but more than ever, people started to wonder: Is it time to move?

Oil and gas companies took heat from investors over emissions. In August, Exxon disappeared from the Dow Jones Industrial Average; it had been a member since the company was Standard Oil of New Jersey in 1928. That same month, oil and gas companies shrunk to become the lowest-weighted component of the S&P 500; in 2008, it was the component’s second-largest sector, right after information technology.

For European supermajors, change includes commitments to significantly or even wholly reduce greenhouse gas emissions while also coming to terms with a future of falling oil demand. For US oil majors, that path is less clear, but capital is having its say. Exxon, long dismissive of both specific emissions reduction strategies and climate change in general, now faces two activist campaigns calling for, among other things, a reckoning with what investors see as an unsustainable emissions trajectory.

A year filled with extreme weather meant a hefty price tag: Insurance firm Aon estimates that at least 25 separate billion-dollar weather disasters unfolded across the United States this year. “The United States has endured one of its costliest years for weather disasters on record and is facing an economic toll that will exceed $100 billion,” Steven Bowen, head of catastrophe insight at Aon, wrote in an email.

A brutally cold dome of high pressure across eastern Asia has produced what may be the highest barometric pressure readings ever documented on Earth. At 7 am local time on Tuesday, the mean sea-level pressure at Tsetsen-Uul, Mongolia, rose to 1,094.3 millibars, or 32.31 inches. The high pressure was accompanied by a bone-chilling temperature of minus-49.9 degrees F.

4. The global economy and the coronavirus

Economic shocks like the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 only arrive once every few generations, and they bring about permanent and far-reaching change. The world economy is well on the way to recovery from a slump the likes of which barely any of its 7.7 billion people have seen in their lifetimes. Vaccines should accelerate the rebound in 2021. But other legacies of Covid-19 will shape global growth for years to come. Some are already discernible. Robots’ takeover of factory and service jobs will advance, while white-collar workers get to stay home more. There’ll be more inequality between and within countries. Governments will play a larger role in citizens’ lives, spending—and owing—more money.

United States: US coronavirus cases crossed the 20 million mark on Friday as officials seek to speed up vaccinations and a more infectious variant surfaces in Colorado, California and Florida. Since Thanksgiving, the US has seen a spike in the number of daily COVID-19 fatalities, with 78,000 lives lost in December. A total of more than 350,000 have died of COVID-19, or one out of every 950 US residents, since the virus first emerged in China late in 2019. New US jobless applications remain elevated at 787,000, but down 19,000 from the previous week.

China: The economy finished 2020 with a 10th consecutive month of expansion in its manufacturing sector, capping a dramatic year that saw the country’s factories incapacitated by the pandemic, only to roar back as a growth engine for China and the world. The economy also showed strength outside its factories. China’s nonmanufacturing PMI, which covers services like retail, aviation, and software and the real estate and construction sectors, came in at 55.7 in December. Though that reading was down from 56.4 in November, it marked the 10th month of expansion and remained near the highest levels in more than a decade.

Taken together, the robust finish to the year is likely to affirm economists’ forecasts for gross domestic product growth in the fourth quarter and full year of more than 6 percent and 2 percent, respectively. It also suggests a strong start to 2021, with economists both inside and outside the government projecting economic growth of 8 percent or more in the coming year. China is on track to overtake the US to become the world’s biggest economy in 2028, five years earlier than previously estimated due to the two countries’ contrasting recoveries from the COVID-19 pandemic, a think tank said.

Inside China, Mr. Xi’s authority is increasingly seen as absolute. He has sidelined rivals, silenced dissidents, and bolstered his popularity by promoting a resurgent China unafraid to assert its interests. The biggest challenge to his vision for China comes not from within its borders but from other parts of the world, in nations whose views of Beijing have dramatically changed in just a few years.

Countries that once avoided upsetting Beijing are moving closer to Washington’s harder and largely bipartisan stance—to curb Chinese access to customers, technology, and sensitive infrastructure. Australia, economically dependent on China, became one of the first countries to block Huawei Technology and led global calls to investigate China’s initial handling of the coronavirus. Once a pillar of the world’s nonaligned movement, India is expanding military cooperation with the US and its allies as it fights with China over contested borders.

Europe now trades roughly as much with China as America and is on the brink of concluding an investment pact with Beijing to deepen those economic links. At the same time, the continent has installed new barriers to Chinese acquisitions and technology.

On Monday, the Trump administration strengthened an executive order barring US investors from buying securities of alleged Chinese military-controlled companies, following disagreement among US agencies about how tough to make the directive.

China’s growing reliance on imports of fossil fuels is a major headache for Beijing. Therefore, increasing domestic production is high on the agenda. Despite some successes in exploration and production activities, import reliance is expected to rise over the next couple of years. Beijing has instructed its three domestic energy champions PetroChina, CNOOC, and Sinopec to increase domestic resources spending. In the next five years, these companies have vowed to invest $77 billion, which is a growth of 18 percent year-on-year.

China has taken measures to secure natural gas, electricity, and coal supplies ahead of another expected cold snap in the coming days. The move comes after China faced energy shortages and price hikes earlier in December in several provinces due to a sharp drop in temperatures that coincided with a faster-than-expected recovery in energy demand on the back of a rebound in economic activity. The cold snap is forecast to hit a broad swathe of the country’s central, eastern, and northwestern regions starting from Dec. 28th.

China imported 6.61 million mt of LNG in November, up 31.6 percent month on month and 1.6 percent higher year on year on rising domestic demand despite higher prices. Lower temperatures stimulated higher consumption from household users, and demand from industrial users increased due to more orders in the Christmas season, market sources said.

European Union: The UK is in a “hazardous situation” in its battle against coronavirus, facing a “grim and depressing picture” of rising infections and deaths as millions more were placed under the tightest tier of restrictions. The bleak picture painted on Wednesday by Jonathan Van-Tam, England’s deputy chief medical officer, followed news of the regulatory approval of the Covid-19 vaccine from Oxford University and AstraZeneca, which has raised hopes.

That optimism faded as the UK recorded 981 coronavirus related deaths, the highest daily figure since April. Infection rates soared to 50,023 new cases. The alarming surge in deaths spurred new measures to limit the spread of the virus. After the Christmas break, the return of secondary schools has been delayed as ministers announced that almost four-fifths of England would be living under the most stringent tier 4 restrictions by Thursday. Mr. Johnson warned that the measures could last until April.

Cases of the more contagious variant of Covid-19 first identified in the UK have been confirmed in several European countries, Canada, the US., and Japan. Infections linked to people who arrived from the UK were reported in Spain, Switzerland, Sweden, and France. Japan is to ban most non-resident foreign nationals from entering the country for a month starting Monday.

On the day the UK made its final break with the European Union, ports were clear of truck backups, goods were moving smoothly, and grocery-store shelves were well stocked. Even so, UK businesses that rely on some $1.6 billion worth of products crossing the border each day are taking no chances. Brexit is real.

Britain long played a unique role within the EU, as a nuclear power and permanent UN Security Council member with Washington’s ear. It was also a budget hawk that insisted on keeping the bloc’s spending in check. Some EU officials worried that the UK’s exit from the bloc would weaken a union that had been under pressure since Britons voted in 2016 to depart. That vote confronted the EU with the risk of disintegration and strengthened Eurosceptic movements.

Instead, as the UK leaves, the EU has regained confidence, helped by a revived Franco-German partnership and encouraged by the Biden administration’s arrival in Washington. Meanwhile, Paris, now the bloc’s dominant foreign-policy actor, is driving the debate on everything from relations with Washington and Moscow to expanding the EU’s military capabilities.

Russia: More than 80 percent of the excess deaths in Russia during 2020 are linked to the coronavirus pandemic. There were almost 230,000 additional deaths between January and November this year compared to 2019 – which would give Russia a total coronavirus death toll of more than 186,000. The revised total is more than three times higher than the estimated 55,000 fatalities acknowledged by Russian authorities. Only two other countries – the US and Brazil – have reported more deaths during the pandemic. Russia has a population of 144 million, less than half that of the US, so the new death toll attributed to the virus is more in keeping with its size and the efforts, or lack thereof, it has been making to control the virus.

Russia is stepping up work on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline before the US tightens sanctions against the controversial project designed to feed more natural gas into Germany. Construction of the 764-mile pipeline reached a milestone on Monday with the completion of pipe-laying in German’s exclusive economic zone. Among next steps is resuming work in Denmark’s part of the Baltic Sea where most of the remaining sections of the 157-kilometer link will be located.

Progress on the link is a victory for Russian President Vladimir Putin and the nation’s gas export champion, Gazprom. When complete, the project will allow Russia to expand deliveries of gas to Europe and circumvent the traditional transport corridor through Ukraine. The US and Eastern European nations say Nord Stream 2 will make Germany and the European Union too reliant on Russian gas.

The number of passengers flying on Russian airlines in November fell 47.9 percent year-on-year. Rosaviatsia added that passenger traffic had dropped 46.2 percent in year-on-year terms between January and November to 64.14 million people. Russia grounded international flights earlier this year because of the coronavirus pandemic but has since resumed specific routes.

India: New Delhi, India’s capital city, seeks to shed its onerous contracts with power plants in order to reduce costs and free up funds for clean energy. Tata Power Delhi Distribution, which retails electricity to customers in New Delhi, has begun talks with Delhi’s provincial government and the federal power ministry to get some of its contracted thermal power re-allocated to other states. The company also plans to oppose any lifetime-extension plans for aging plants it has contracted to buy electricity from.

The effort underscores how India’s electricity sector continues to struggle with debt and overcapacity after a massive build-out of plants to power a surge in economic activity that never fully materialized. The pandemic has accentuated the problem, leaving nearly half of India’s thermal power capacity idled, with the cost overhang impeding investment toward renewables and grid improvements.

5. Renewables and new technologies

Solid-state batteries have long been seen as a way of breaking through performance limitations associated with electric vehicles. The promise of solid-state is to get rid of battery liquids, and with it, the fire risk. Moreover, “lithium-metal” cells being developed by QuantumScape, among others, combine the lithium component with the anode, further reducing bulk and potentially delivering more power at a lower cost. Relatively high batteries’ cost has long held back EVs.

Other advantages of a solid-state include rapid charging and longer life expectancy. QuantumScape said in December that its cell as tested could be recharged to 80 percent in 15 minutes and retained more than 80 percent of its capacity even after 800 charges. Such numbers would make owning an EV similar to those of owning a gas-powered one today.

While many in the battery industry see solid-state as the most likely technology of the future, Tesla Chief Executive Elon Musk is a prominent exception. Solid-state wasn’t among the many developments discussed in the company’s September “battery day.” Musk told analysts that removing the conventional anode “is not as great as it may sound” to deliver space savings in the cell.

Tesla has time on its side if it needs to change tack. Toyota probably has the most advanced solid-state batteries today and is targeting a mass-produced model by 2025. But the technology likely won’t be cost-competitive with today’s batteries until the late 2020s at the very earliest.

Oxford University researchers have developed a method to convert CO2 directly into aviation fuel using an inexpensive iron-based catalyst. The catalyst shows a carbon dioxide conversion through hydrogenation to hydrocarbons in the aviation jet fuel range of 38.2 percent, with a yield of 17.2 percent. The conversion reaction also produces light olefins—ethylene, propylene, and butene—totaling a yield of 8.7 percent. Within three years, the Oxford team wants to complete a transatlantic trip based on its synthetic fuel.

Moscow is trying to find a new purpose for its energy industry by early investments in hydrogen technologies. The energy ministry is working on a hydrogen strategy in cooperation with foreign partners in Japan and Germany and the country’s primary energy firms — Rosatom, Novatek, and Gazprom. With the support of Moscow, each of these firms is looking into different technologies to produce and export the hydrogen. According to deputy prime minister Alexander Novak, “experts say that hydrogen may constitute 7 to 25 percent of the global energy balance by 2050, as soon as the issues of high production costs and the challenges related to transportation are resolved.”

6. The Briefs (date of the article in the Peak Oil News is in parentheses)

The North Sea oil and gas industry enters 2021 picking up the pieces after a price collapse. With optimism, it has more to give as new companies, projects, and exploration help navigate the energy transition. The industry emerges from 2020, having broadly maintained production and encouraged by recent oil price rises as well as government backing. (12/29)

Nigeria may lose up to 38 percent of its deepwater oil production under the terms of the proposed new Petroleum Industry Bill. This could happen by 2025. The country’s parliament plans to pass the new law in the first quarter of 2021. However, according to the industry, the bill in its current form will hurt rather than help Nigeria’s oil production. (12/30)

Angola: This year will mark the fifth consecutive year that Angola’s production decreases. In the past five years, it has slid by an average of some 7% annually. (12/30)

In Brazil, the crash in worldwide oil prices did not impede the nation’s massive oil boom. Growing demand for lighter, sweeter crude oil grades from Asia, coupled with stronger than expected domestic demand for gasoline, are buoying Brazil’s oil industry. Overall, October production fell a modest 2.6% year over year to an average of just under 3.7 million oil-equivalent barrels daily. (12/30)

Colombia’s economy likely declined 8% or more during 2020. For a decade, hydraulic fracturing has been positioned as a means of resolving many of the issues confronting Colombia’s hydrocarbon sector and petroleum-dependent economy. There are signs after nearly ten years that fracking could become a reality for Colombia’s economically crucial oil industry. (12/31)

During the weekend, Mexico issued new rules that would limit fuel imports of private firms in a controversial move seen as boosting the dominant position of state oil firm Pemex. Despite mounting debts and declining crude production, Pemex is focused on an US$8-billion refinery planned for President López Obrador’s home state of Tabasco. (12/29)

The US oil rig count decreased by 7 to 293, while the gas rig count rose by 1 to 114, according to Enverous. The combined count of 407 rigs was down more than 50% year-over-year. (1/1)

More export capacity: A new dock in the Corpus Christi Ship Channel will accommodate the berthing and loading of two vessels simultaneously. Moreover, STG had loaded its first very large crude carrier (VLCC) tanker with crude oil for export. (1/1)

ExxonMobil is on track to book another quarterly loss this year—its fourth consecutive loss in 2020—announcing on Wednesday that it expects to book a massive up to $20-billion write-down for Q4. (1/1)

Battery storage is beginning to threaten coal and natural gas power plants as utilities everywhere increasingly plug them into the electric grid. Indeed, there’s an unfolding trend whereby cheap grid-scale batteries are beginning to replace fossil fuel power plants as the more economical option for supplying extra power during times of peak usage thanks to falling costs. (12/29)

Shuttering nukes: Millions of homes and factories in Sweden could get hit by rising power costs after the nation’s oldest nuclear reactor generates its last megawatt on Thursday. Since the decision five years ago to close a fourth nuclear plant in seven years, the energy debate has turned from discussing what to do with a massive glut of power to deal with a capacity shortage in many major cities. The next closure will strain supply to the populous south. (12/29)

For Vietnam, Japan approved a plan to help finance a long-planned coal power plant, despite the pledge to curb overseas investments in dirtier technology and cut emissions at home. The Japan Bank for International Cooperation agreed to provide $636 million of financing. (12/31)

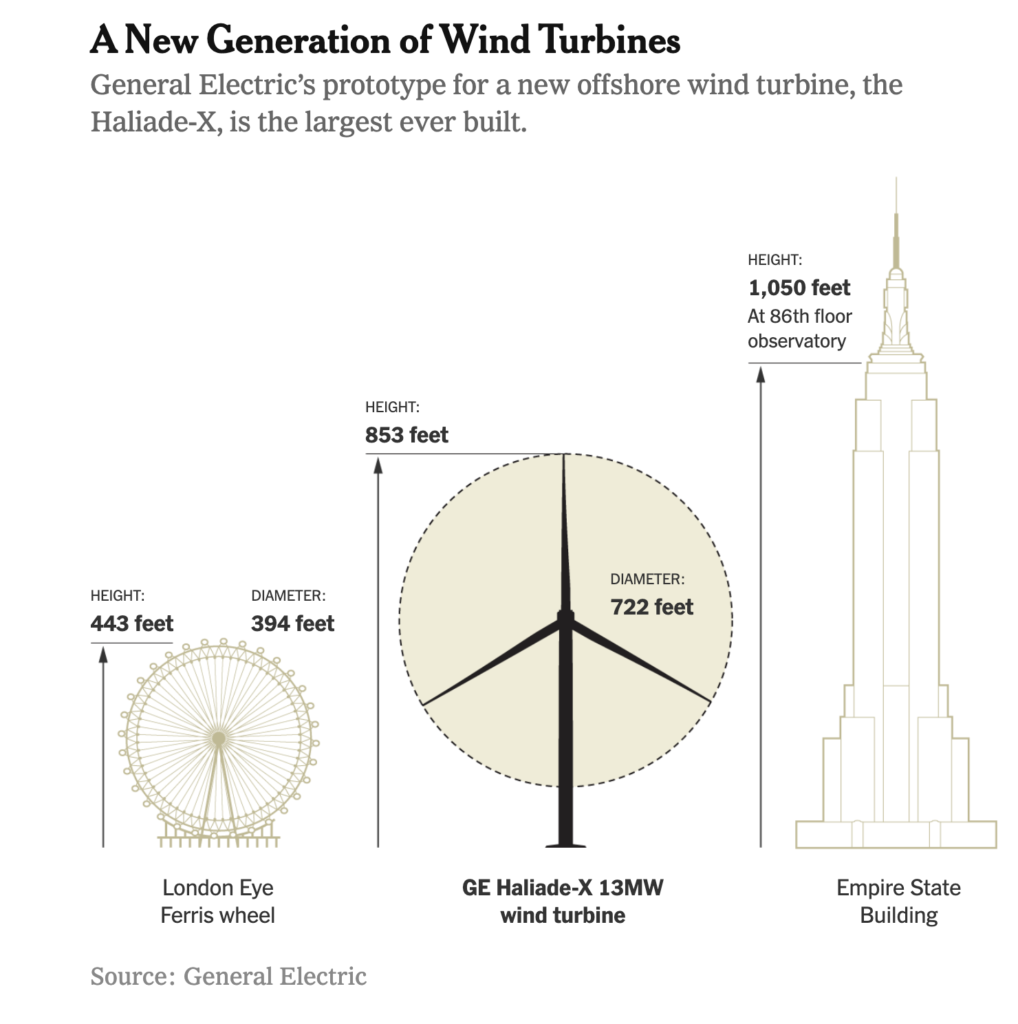

BIG wind: In the Netherlands, GE’s giant machine, which can light up a small town, is stoking a renewable-energy arms race. Twirling above a strip of land at the mouth of Rotterdam’s harbor is a wind turbine so large it is difficult to photograph. The turning diameter of its rotor is longer than two American football fields end to end. (1/1)

More wind: Azerbaijan signed agreements with Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power to construct a 240-megawatt wind park. Azerbaijan’s Energy Minister Shahbazov and his Saudi counterpart attended the signing ceremony via video conference. Shahbazov said Azerbaijan plans to increase clean energy in electricity generation to 30% over the next decade. (12/31)

Battery R&D: Cost and duration are the two big problems that need to be solved to make large-scale battery storage a reality and renewables the dominant form of energy generation. Scientists from the Joint Center for Energy Storage Research, a division of the Dept. of Energy, use computational screening and robots to develop a new generation of batteries that may someday replace the dominant lithium-ion technology. (1/1)

According to a Danish startup company, floating barges fitted with advanced nuclear reactors could begin powering developing nations by the mid-2020s. Seaborg Technologies believes it can make cheap nuclear electricity a viable alternative to fossil fuels across the developing world as soon as 2025. (12/30)

Blue ammonia: In east Asia, Japanese firms partner on a joint feasibility study of a blue ammonia value chain between eastern Siberia and Japan. The project aims to establish a future blue ammonia value chain on a commercial scale. Blue Ammonia is CO2 -free ammonia produced by conventional ammonia production processes with CCS (CO2 capture and storage) to isolate CO2 into underground reservoirs. (1/1)

Hydrogen train: Scottish Enterprise, Transport Scotland, and the Hydrogen Accelerator, based at the University of St Andrews, have appointed Arcola Energy and a consortium of industry leaders to deliver Scotland’s first hydrogen-powered train. (12/31)

Jet fuel from CO2? Last week, researchers at Oxford University published a study on a novel scientific process that would transform carbon dioxide in the air into an alternative jet fuel that could power existing aircraft. Instead of adding to the amount of carbon in the air, the Oxford experiment would result in a “carbon-neutral” emission by plane. A jet would essentially extract the gas from the air while on the ground and re-emit it via combustion while in flight.