Editors: Tom Whipple, Steve Andrews

Quotes of the Week

Well before shutdown orders, restaurant reservations were plummeting. Electricity usage, which falls when office buildings and factories empty out, was dropping, too. Public transit in many cities was in free fall. So was the number of air travel passengers passing through TSA checkpoints. Such data, combined with opinion polling today, suggests that Americans who were turning off the economy on their own may not readily reopen it soon — even if officials say it’s OK to.”

Emily Badger and Alicia Parlapiano, The New York Times

“There’s just no evidence that this partial reopening in Georgia has significantly changed anything in the economy.”

John Friedman, an economist at Brown University

Graphics of the Week

| Contents 1. Energy prices and production 2. Geopolitical instability 3. Climate change 4. The global economy 5. Renewables and new technologies 6. Briefs |

1. Energy prices and production

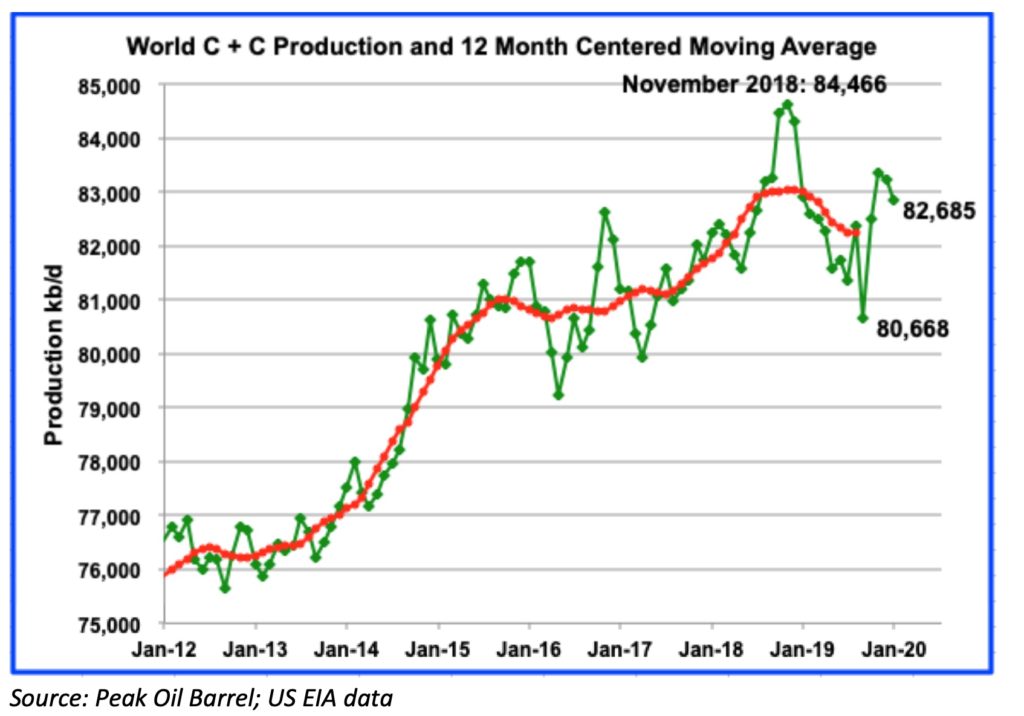

Oil posted its first back-to-back weekly gain since February amid optimism that production cuts are beginning to eat into the massive supply glut. Futures in New York climbed 25 percent to circa $25 and $31 in London. Drillers are cutting production rapidly in response to ruinous crude prices. The number of US rigs drilling for oil fell to a level not seen since before the shale-oil revolution began at the beginning of the last decade. Last week’s data from the EIA supported the price move as US gasoline supplied, an indicator of consumption, rose by the most in almost two years last week, and nationwide crude production declined for a fifth straight week to the lowest since July 2019.

The question at the minute is whether the price rally will continue amid a spreading pandemic and a growing oil supply glut. The answer to this depends mostly on where the virus situation goes during the next few weeks. In the US, President Trump is pushing governors and companies to open for business no matter the cost. However, polls show the public is not as yet willing to undergo the risks of returning to regular economic activity. Across Europe, several countries that have been badly hit by the virus are starting to lift restrictions, but information as to the course of the infection will not be available for a couple of weeks. Iran lifted restrictions two weeks ago and is already reporting higher levels of hospitalizations.

If a spike in coronavirus cases occurs in the next few weeks to the point where it overwhelms hospital facilities, it likely that more widespread restrictions on economic activity will be reimposed, and the demand for oil will fall. The possibility that a critical mass of the public is not willing to leave home as yet could force many companies to close or cut back on their activity again for lack of customers or workers.

A lot of crude oil is still being pumped into storage, creating the possibility that any price-gains prompted by slowly recovering demand will be limited. The market remains well oversupplied, but OPEC+ production cuts and curtailments, mostly of shale oil production, should moderate the supply overhang. As excess oil cannot be flared the way natural gas is, shutdowns of more wells will be mandatory.

Over the long run, months or years, the question will be how much damage the virus will inflict permanently on the global economy and on the ability of oil companies to eventually increase production profitably. Likely, the era where millions of barrels will be produced at a loss, financed by Wall Street and low-interest rates, is over. If the balance between supply and demand reverses, shortages could appear again, and talk of $100+ oil could still revive. For the short term, this seems highly unlikely. We are still many months from knowing how the course of the coronavirus will evolve. Until then, predictions that oil will reach $50, $70, or $100 again are meaningless.

It is too early to determine how much the demand for crude oil and other energy liquids has fallen from its pre-virus peak of 100 million b/d. In the last weeks of March, when shut-ins were at their peak, the consensus seemed to be that the drop in demand was around 30 million b/d, with a few international oil traders talking about 40 million. We do know that US gasoline consumption was down about 50 percent and that the Chinese stepped up imports of ultra-cheap oil for whatever storage space they had available.

Consulting firm IHS Markit expects oil demand in the second quarter to be 22 million b/d less than a year ago. “When it comes to the where, why, and how of production cuts, the wide range of technical, logistical, regulatory, contractual, and financial conditions means there is no single set of answers. But under these market conditions, it is pretty clear where production will be cut. Nearly everywhere,” said Paul Markwell, vice president, global upstream oil and gas at IHS Markit.

America and OPEC members, as well as countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States—particularly Russia—are expected to be the source of most of the production cuts. The US is on track to cut 1.7 million b/d, according to Reuters calculations of state and company data. Plains All American Pipeline says US and Canadian oil producers are curbing as much as 4.5 million b/d. Moscow says the US will cut production by 2-3 million b/d. It will be at least two months before a reasonably accurate picture of how much of a cut is taking place will come into focus.

Shutting an oil well is effortless these days. Thanks to submersible electric pumps, in many cases it can be done with a few taps on an iPhone. Figuring out which to shut, and for how long, is the hard part. Companies are deciding everything from which wells should be shut first to which should be closed for good, what the costs are, how easy it will be to restart some of them, and what fields may be too porous to handle a shutdown if you ease operations across hundreds, or even thousands, of wells at once. The trick is not to close in oil that may be lost forever.

The world’s oil supply isn’t falling quickly enough to keep up with the decline of empty storage space. Tanks around the world are rapidly filling with crude. The overwhelming glut is threatening one of the world’s vital industries and could prolong the economic fallout from the coronavirus.

Not only US storage facilities, but the volume of oil products held in storage at Fujairah in the UAE jumped to the highest level on record. Their stocks rose 6.3 percent last week to 26 million barrels, with the most significant build seen in middle distillates, including jet fuel, according to data released by the Fujairah Oil Industry Zone.

There are so many factors at play in the coronavirus/energy crisis that it is impossible to make a responsible judgment about the rest of the year. If the last three months have taught anything, it is that the most accurate projections can be completely wrong. The pandemic could peter out this year or still be the most crucial factor in the economic situation until a vaccine is widely disseminated a year or two from now.

How will industries such as airlines, cruises, movie theaters, the sports industry, restaurants, and even major oil companies fare during a prolonged shutdown? Will the economic slump be so severe that gasoline, once the price eventually snaps back, is no longer affordable for many? Serious questions about our future abound.

2. Geopolitical instability

With every country involved in an international confrontation or domestic instability suffering from the coronavirus and low oil prices, there is little time or money to pursue political goals. The US is removing Patriot antimissile systems from Saudi Arabia and is considering reductions to other military capabilities—marking the end, for now, of a large-scale military buildup to counter Iran, according to US officials. While the US and Europe have done a reasonable job reporting the damage caused by the virus, most countries do not have the infrastructure or the desire to publicize how badly they have been hit by the pandemic.

Iran: New infections from the coronavirus surged in Iran two weeks after it began easing restrictions on its population. Tehran closed off religious sites and locked down parts of its economy in March after emerging as the most prominent hot spot in the Middle East. In late April, the government allowed bazaars and shopping malls to re-open and eased restrictions on travel after the spread of the virus slowed for several weeks. That re-opening came despite Iranian health professionals’ warnings of a potential second wave of infections.

Two weeks later, the pace of infections in the country started to accelerate again, with the health ministry reporting 1,485 new cases on Thursday, up from about 800 on Saturday. Official cases surpassed 100,000 last week in the country, where nearly 6,500 people have died from Covid-19. Despite the risk, the country moved forward with plans to re-open mosques and resume Friday prayers in 107 towns two months after they were suspended. That permission applies to areas Iranian officials have classified as “low-risk.” Ten provinces and all provincial capitals, including Tehran, won’t be allowed to re-open mosques yet.

Construction is now underway on a new oil pipeline that will be able to transport large quantities of oil and petrochemicals from its major oil fields to the port of Jask on the Gulf of Oman. This 42-inch pipeline will be crucial to Iran’s ability to continue to circumvent US-led sanctions and to consolidate its customer base in Asia.

Iraq: Iraq’s Parliament chose an American-backed former intelligence chief as the new prime minister on Thursday, giving the country its first real government in more than five months as it confronts an array of crises. The prime minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, 53, who has a reputation for pragmatism, is also seen as an acceptable choice to Iran, the other significant foreign power competing for influence in Iraq.

The new prime minister wants to restore the oil market share of OPEC’s second-largest oil producer and renegotiate contracts with IOCs, according to his program. The program, as published on the parliament’s website, says Iraq should open “serious negotiations” to restore its oil export share that has shrunk lately. Iraq took the biggest hit to production for OPEC members in April, as low fuel demand and a lack of product storage space forced its refineries to severely lower crude runs, according to the latest S&P Platts OPEC survey. Production was 4.54 million b/d in April.

Unlike other fellow producers in OPEC, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which pumped at record levels in April, Iraq was not able to open the taps despite the expiry of the old OPEC+ cuts agreement in March. Iraq’s state oil marketer SOMO struggled in April to sell crude to India, one of its biggest customers. Iraq also is grappling with the outbreak of the coronavirus and lockdowns that have taken a toll on its oil industry and forced Malaysia’s Petronas to evacuate staff in March and stop production from the southern oil field of al-Gharraf, which pumped some 90,000 b/d.

The Iraqi government and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) are relaxing their strict anti-pandemic lockdown, despite fears of a second wave of infections, as border crossings with Iran re-open. The measures to combat the spread of COVID-19 were put in place more than two months ago. These measures included airport and border closures, strict curfews, and significant modifications to oil worker shifts.

A combination of the pandemic lockdown and low oil prices has pushed Iraq’s economy to the brink of collapse. Experts say renewed social unrest is imminent unless social reforms do not meet the need for food of millions of Iraqis. It is this situation that has forced Baghdad to lift the social restrictions despite the likelihood of increased infections.

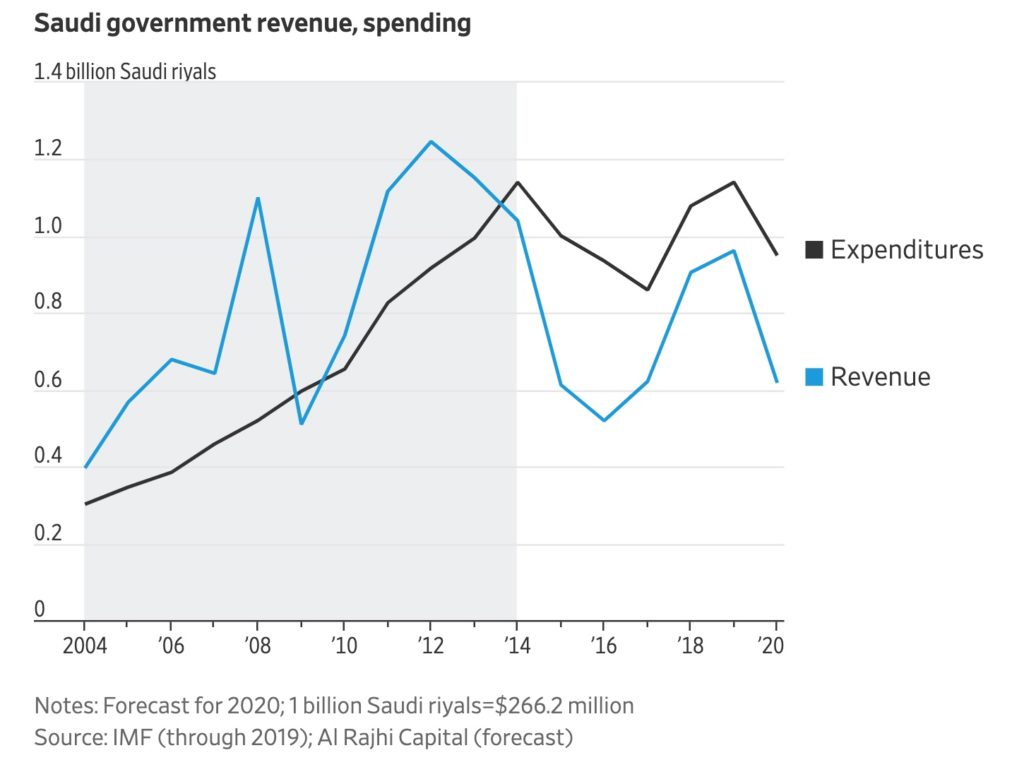

Saudi Arabia: The government is taking unprecedented measures to cushion the blow of low oil prices and the pandemic, as the monarchy seeks to extricate the kingdom from its worst financial predicament in decades. State-owned oil firm Saudi Aramco has further slashed production, and dozens of oil-laden supertankers float idly at sea. Smaller oil revenues mean the world’s top oil exporter will have to draw down $32 billion from foreign reserves this year and borrow billions more from debt markets. Government spending is now as high as during the “magic decade” between 2004 and 2014 when oil prices were above $100 a barrel.

Businesses that had positioned themselves for a new Saudi Arabia under Prince Mohammed’s social and economic overhauls—coffee shops, gyms, cinemas, and travel agencies—are scrambling for government lifelines to stay afloat. The crisis also is forcing spending cuts on the prince’s transformation of the economy away from oil.

“The kingdom has not faced such a crisis—neither health-wise nor financially—for decades,” Finance Minister Mohammed al-Jadaan told government-owned broadcaster Al Arabiya last week. “As long as we do not touch the necessities of the people, all options are open.”

Moody’s downgraded its assessment of Saudi Arabia’s credit rating to negative, citing the severe shock to global oil demand and the pandemic. The kingdom requires oil prices of $76 a barrel to balance its budget this year, according to the IMF. Brent crude, the global benchmark, was at $31 over the weekend.

3. Climate change

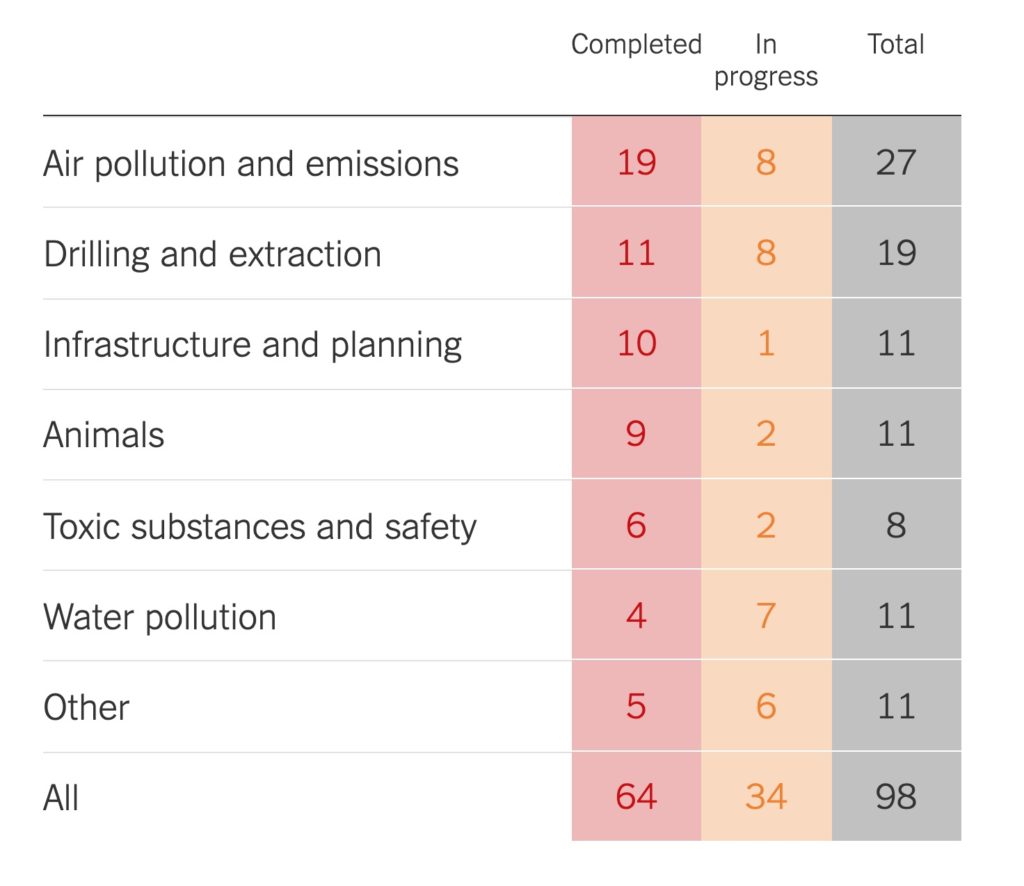

After three years in office, the Trump administration has dismantled most of the significant climate and environmental policies the president promised to undo. Calling the rules unnecessary and burdensome to the fossil fuel industry and other businesses, his administration has weakened Obama-era limits on planet-warming carbon dioxide emissions from power plants and cars and trucks and rolled back many more rules governing clean air, water, and toxic chemicals. Several major reversals have been finalized in recent weeks as the country has struggled to contain the spread of the new coronavirus.

In all, a New York Times analysis, based on research from Harvard and Columbia Law Schools and other sources, counts more than 60 environmental rules and regulations officially reversed, revoked or otherwise rolled back under Mr. Trump. An additional 34 rollbacks are still in progress.

With elections looming, the administration has sought to wrap up some of its biggest regulatory priorities quickly, said Hana V. Vizcarra, a staff attorney at Harvard Law School’s Environmental and Energy Law Program. Further delays could leave the new rules vulnerable to reversal under the Congressional Review Act if Democrats can retake Congress and the White House in November, she said.

The Trump administration is signaling it is about to offer a lifeline to solar and wind projects battered by the coronavirus pandemic. In a letter sent to senators Thursday, the Treasury Department said it is considering ways to let the solar, wind, and other alternative energy developers continue to qualify for tax incentives. These would be critical for paying for the building of wind turbines and solar panel arrays – even if construction is put on hold. The decision is a coup for businesses trying to move the country toward cleaner energy but facing potential delays in development and funding due to the coronavirus pandemic.

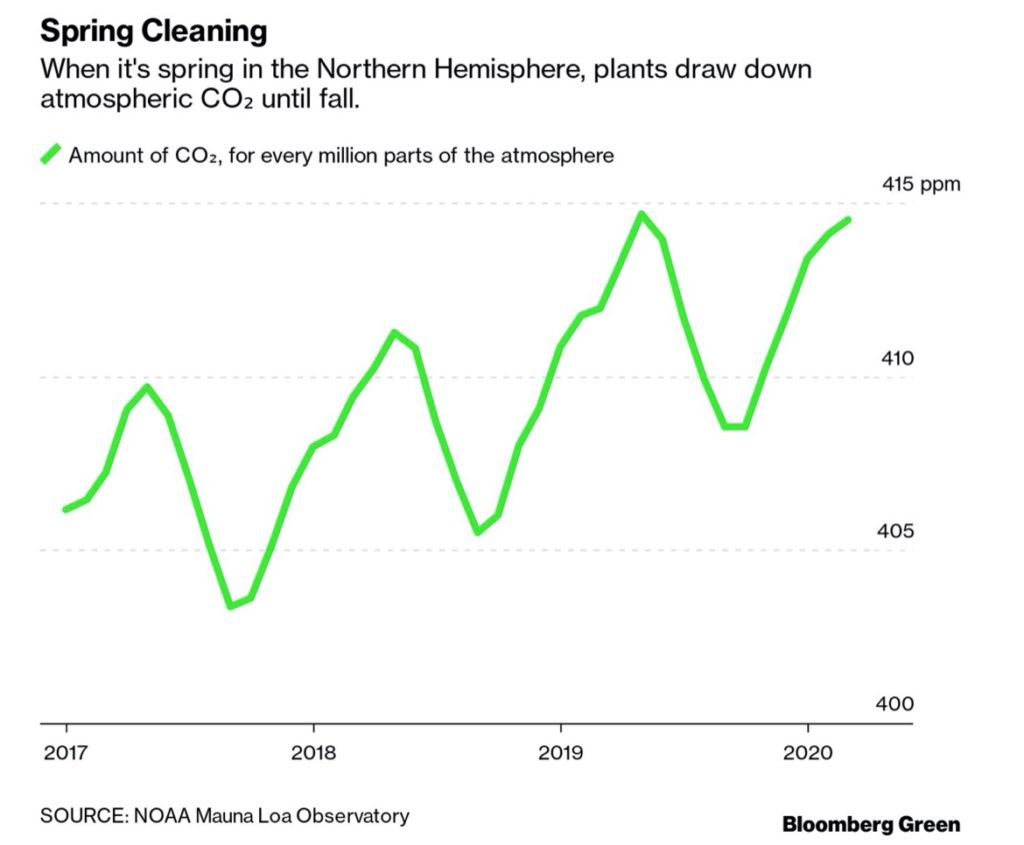

Carbon-dioxide levels always drop throughout the spring and summer in the Northern Hemisphere, as plants absorb carbon dioxide. This seasonal effect is occurring as pandemic lockdowns have stopped billions of people from driving and working, slashing fossil-fuel use, and lower carbon-dioxide emissions. “If we were to continue like this for months, instead of weeks, we would see a drop in carbon emissions that we haven’t seen in my lifetime,” said Rob Jackson, a professor at Stanford University and chair of the Global Carbon Project. “And probably since the end of World War II. That’s where we’re heading.”

Not long after China began to close down economic activity because of Covid-19, analysts began to estimate how much climate pollution would be prevented due to quarantines. The conclusion so far: about 25%, and only temporarily.

An early study from Harvard University, linking dirty air to the worst coronavirus outcomes, has become a political football in Washington. Presidential candidates, agency regulators, oil lobbyists and members of Congress from both parties are using the preliminary research to advance their political priorities — well before it has a chance to be peer-reviewed. The stakes are high because the study’s tentative findings could prove enormously consequential for both the pandemic’s impact and the global debate over curbing air pollution.

The researchers found that air is making the pandemic even more deadly as the study claims to show that coronavirus patients living in counties with higher levels of air pollution, were more likely to die from the respiratory disease. If these findings prove to be true, they should help convince the Trump administration to cut air pollution and stop rolling back environmental regulations.

Temperatures in April were on par with the previous warmest April on record four years ago, with extremely high temperatures in some parts of Europe, Greenland, and Antarctica. Above-average global temperatures meant April was just 0.01 degrees Celsius cooler than April 2016, a difference considered statistically “insignificant.” Global temperatures were 0.7 degrees Celsius warmer than the average of April between 1981 and 2010. Temperatures well above the historical average also were found in Siberia, the Alaskan coast, the Arctic Ocean, Mexico, Western Australia, and parts of Greenland and Antarctica. Canada and some parts of southern and south-eastern Asia were cooler than usual.

Sea-level rise is faster than previously believed and could exceed one meter by the end of the century unless global emissions are reduced, according to a survey of more than 100 specialists. Based on new knowledge of climate sensitivity and polar ice melt, the experts say coastal cities should prepare for an impact that will hit sooner than predicted by the United Nations and could reach as high as five meters by 2300.

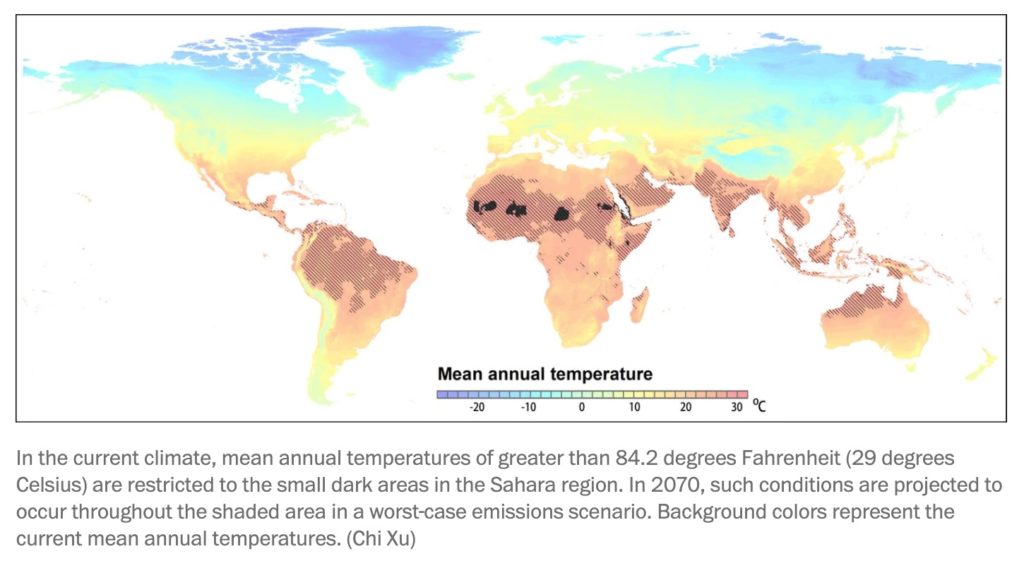

In a new finding of the planet’s rapidly warming climate, a study finds that for every 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit (1 degree Celsius) of global average warming 1 billion people will have to adapt or migrate to stay within climate conditions that are best suited for crop production, livestock, and a sustainable outdoor work environment.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on Monday, breaks new ground by quantifying the temperature range society is most adapted to and projecting how climate change will push people outside it.

“What we have looked for is humanity’s sensitivity to warming, and that is about 1 billion people in trouble per degree [Celsius] of warming,” said study co-author and Dutch research ecologist Marten Scheffer of the Santa Fe Institute and Wageningen University. Scheffer and his colleagues examined the history of global temperature, human population and land-use estimates from the mid-Holocene period, starting about 6,000 years ago, to 2015. They found that people, crops, and livestock have heavily concentrated in a narrow band of relatively constrained climate conditions. This range referred to in the study as the human “climate niche,” has remained unchanged over the past 6,000 years.

Projecting into the future using a scenario with high emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, the researchers found that the position of the human climate niche is expected to change more in the next 50 years than it has during the past 6,000. Such a shift would leave 1 billion to 3 billion people outside the climate conditions that have nurtured human society to date.

4. The global economy

A substantial majority of people around the world want their governments to prioritize saving lives over restarting economies, a global survey found. Overall, 67 percent of the 13,200 people interviewed between April 15 and April 23 agreed with the statement: “The government’s highest priority should be saving as many lives as possible even if it means the economy will recover more slowly.” Just one-third backed the assertion: “It is becoming more important for the government to save jobs and restart the economy than to take every precaution to keep people safe.” The study was based on fieldwork carried out in Canada, China, France, Germany, India, Japan, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the US.

This result suggests that the moves underway in the US, Europe, the Middle East, and elsewhere to reduce restrictions on people’s movements and to congregate may not be as successful in the short run as their sponsors hope.

A vaccine would be the ultimate weapon against the coronavirus. However, the truth is that a vaccine probably won’t arrive any time soon. According to the New York Times, clinical trials rarely succeed. The record for developing an entirely new vaccine is at least four years. This is more time than the public or the economy can tolerate social distancing, which is why President Trump is demanding that the standard time be compressed to months, not years.

There are already some 95 vaccines related to Covid-19 being explored, and fortunately, we already have a head start on the first phase of vaccine development: research. The outbreaks of SARS and MERS, which are also caused by coronaviruses, spurred lots of research. SARS and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, are roughly 80 percent identical. This helps explain how scientists developed a test for Covid-19 so quickly.

The United Nations more than tripled the size of its humanitarian aid appeal on Thursday to help the most vulnerable countries threatened by the coronavirus pandemic, from $2 billion initially sought-just six weeks ago to $6.7 billion now.

The enormous expansion of the appeal, announced by the top humanitarian aid official at the UN, reflected what he described as an updated global plan that includes nine additional countries deemed especially vulnerable: Benin, Djibouti, Liberia, Mozambique, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sierra Leone, Togo, and Zimbabwe, while the peak of the pandemic in the poorest countries is not expected until somewhere between three and six months from now.

United States: As the nation confronts unemployment levels not seen since the Great Depression, Congress and the Trump administration face a pivotal choice: either continue spending trillions trying to shore up businesses or bet that state reopenings will jump-start the economy without causing an unacceptable increase in virus cases. Some 30-40 million Americans are unemployed, and a large share of the nation’s small businesses are shut and facing possible insolvency. Policy errors in the coming weeks could turn the temporary layoffs recorded in April into permanent job losses plunging the country into a deep and protracted recession.

In the weeks before states around the country issued lockdown orders this spring, Americans were already hunkering down. People were behaving in a way that effectively slowed the economy — before the government told them to. That pattern suggests in the weeks ahead that official “openings” will have only limited power to open the economy back up. In the states that have already begun that process, like Georgia, South Carolina, Oklahoma, and Alaska, daily economic data shows only small signs so far that businesses, workers, and consumers have returned to their old routines.

Europe: German factories saw demand collapse in March when measures to contain the coronavirus brought the economy to a sudden halt. Orders fell 15.6 percent from the previous month, the most since data collection started in 1991 and more than economists predicted. While all sectors were affected, investment goods plunged heavily. The European Central Bank sees output in the currency bloc falling between 5 percent and 12 percent this year. As a manufacturing powerhouse, Germany has been particularly affected by factory closures, supply-chain disruptions, and a global erosion of demand.

The European Central Bank has warned that GDP in the bloc could decline as much as 15 percent in the second quarter, telling governments “joint and coordinated policy action” is needed to underpin an eventual recovery. National efforts have allowed companies to furlough more than 40 million workers and provided hundreds of billions of euros in loans, grants, and credit guarantees. A meaningful solution to share the financial burden of those rescues around remains absent.

China: President Trump cast doubt on the future of his “phase one” trade deal with China, one of the most significant accomplishments of his first term, saying that he’s struggling with Beijing in the wake of the global coronavirus pandemic. The President’s remarks contrasted with statements from Chinese and US officials earlier in the day that pledged to create favorable conditions for the implementation of the bilateral trade deal.

Trump has mused about punishing China for the coronavirus outbreak and warning he might ditch the agreement and impose tariffs on China because of the virus. Relations between the Washington and Beijing, strained for years, have deteriorated at a rapid clip in recent months, leaving the two nations with fewer shared interests and a growing list of conflicts.

China has just suffered its first quarter of economic contraction since the 1970s. Millions of jobs have been lost, and the coronavirus pandemic has hampered businesses for more than three months. However, Beijing has yet to match the enormous monetary and fiscal packages rolled out in some of the world’s largest economies, such as Japan, the EU, and the US—where trillion-dollar stimulus included payments to individuals, expanded unemployment insurance, and loans to struggling industries. Beijing’s response has even fallen short of its efforts to address previous economic crises, such as the global financial crisis in 2008 and a sharp slowdown in domestic growth in 2015.

With factories shut down and supply chains paralyzed, “fiscal and monetary policy were useless,” said Yu Yongding, an economist and adviser to Chinese policymakers. “Under this kind of circumstance, even if people want to spend money, they cannot spend.” Now, with the virus mainly under control in China, the question is whether the Chinese consumer will be able to power a robust recovery without the help of a muscular stimulus effort.

But it is unclear how long the recovery will last, and some are arguing that the time has come, with the pandemic mainly under control, for Beijing to open up the fiscal spigots to encourage domestic consumption. That is primarily since exports, traditionally a growth engine for China’s economy now accounting for less than one-fifth of GDP, will face pressure from the coronavirus’s toll in Western countries.

China’s exports rebounded in April to rise 3.5 percent over a year earlier, but forecasters warned that strength is unlikely to last as the coronavirus pandemic depresses global consumer demand. Exports to the United States rose by 2.2 percent. In comparison, imports of American goods fell 11 percent in a sign of weak Chinese industrial and consumer demand despite the lifting of most anti-virus controls, government data showed Thursday. Total exports rose to $200.3 billion, a turnaround from the 13.3 percent contraction in the three months ending in March.

Crude imports for China’s independent refineries further rebounded 8.3 percent to 3.22 million b/d, with Shandong independent refineries booking more cargoes last month. This was mostly in line with the market expectation that April imports were likely to be slightly higher. Looking forward, more cargoes will flood into the Shandong market in late May and June as refineries rushed to book shipments when prices were at all-time lows in March.

Russia: The authorities said on Sunday they had recorded 11,012 new cases of the coronavirus in the last 24 hours, bringing the nationwide tally to 209,688.

Russia’s coronavirus taskforce said 88 people had died in the past day, pushing the national death toll to 1,915. Russian coronavirus cases overtook French and German infections this week to become the fifth highest in the world.

The pandemic, plummeting oil prices, and a decline of confidence in Mr. Putin’s leadership are threatening to erode his efforts to project himself as the only person who can unite Russia’s people and cement the nation’s relevance on the world stage. Russians for years have complained about decaying roads and bridges. Soviet-era hospitals suffer from a shortage of doctors, leading to long waiting times, while many schools are unsafe or poorly maintained. A $400 billion spending plan was supposed to overhaul the country’s infrastructure and create millions of jobs. Still, the Kremlin has acknowledged that falling budget revenues mean it will need to adjust its plans, jeopardizing Mr. Putin’s economic legacy. Putin’s attempts to “Make Russia Great Again” by spending on advanced nuclear weapons and financing foreign adventures in the Middle East have not done much for the Russian people.

The influence of the Russian business tycoons known as oligarchs waned early this century as President Putin consolidated power, transforming them from warring clans to fantastically wealthy families dependent on the Kremlin’s benevolence. Now, the coronavirus crisis presents them with another turning point: the most significant economic threat in decades, coupled with an enormous stress test for the state that makes their wealth possible. And so the oligarchs, with millions of employees and dozens of Russian cities reliant on their enterprises, have become central figures in the national response to the pandemic.

With local health systems buckling, many oligarchs are deploying millions of dollars of their cash, along with their companies’ logistics and procurement capacity, to fight the spread of the illness, while urging slow-moving regional authorities to act with more resolve. In the process, they are revealing the Russian state’s weaknesses, and how much Mr. Putin’s system of governance still relies on informal alliances with business tycoons. The depth of their coffers also puts the oligarchs in position to outlast the pandemic — unlike Russia’s reeling small and midsize businesses.

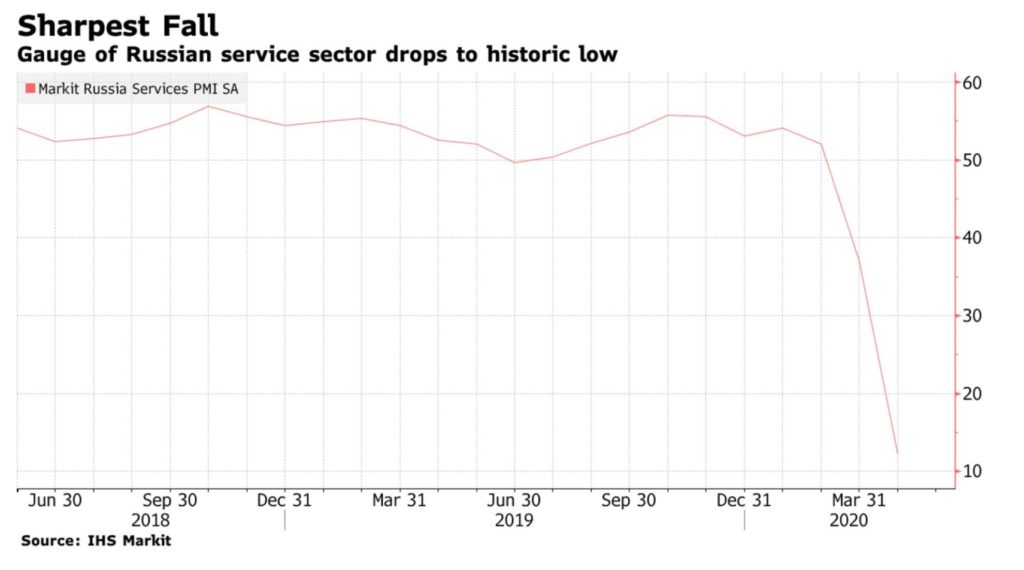

A gauge of Russian services slumped the most since records began in 2001 in the latest sign that the economy of the world’s biggest energy exporter is falling into a deep recession. The Purchasing Managers’ Index for Russia’s service sector plunged to 12.2 in April, down from 37.1 in March, IHS Markit reported on Thursday.

“The sudden shock to business operations became blatantly apparent in April, as new order inflows dried up and firms cut employment at the sharpest rate in the series history,” IHS Markit, said in a report. The data follows a similar slump in manufacturing and warnings from top government officials that financial pressure is mounting. Economic activity contracted by a third since lockdowns were enforced across most of the country at the end of March, Economy Minister Reshetnikov said at a government meeting on Wednesday.

President Vladimir Putin urged officials on Wednesday not to rush in lifting the self-isolation regime, and Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin said it is too early to start thinking about reopening the service sector.

5. Renewables and new technologies

The World Economic Forum recently published a report saying that the energy industry could use this unprecedented disruption of the global economy to consider building a “new energy order.” With much of the world’s energy supply in disarray, this could be an excellent opportunity to dedicate resources, investment, and research and development into renewable energy ventures. As business-as-usual ceases to become an option, “transforming America into a country that runs on clean energy is one way experts hope to alleviate the devastating economic downturn caused by the pandemic.”

One idea is a $2 trillion “green stimulus” package, which “aims to create jobs by dramatically expanding renewable energy capacity and retooling the nation’s infrastructure for the transition away from fossil fuels,” says political economist Mark Paul. “Right now is the ideal time to be investing in renewable energy that can produce millions of family-sustaining wage jobs across the country.”

The executive director of the International Energy Agency (IEA), Fatih Birol, said that the turmoil in the oil sector caused by the COVID-19 pandemic gives governments the perfect opportunity to embrace green energy as a source of jobs that also serves climate goals. In an interview with Reuters, Birol said that not only well-established technologies, such as those behind solar and wind generation, should receive a boost, but also lithium-ion batteries and the use of electrolysis to produce hydrogen from water should be candidates for subsidies and policy support. Besides being the backbone of electric vehicles and electronic devices, li-ion batteries are becoming more and more critical in solar and wind farms to store energy when nature is not doing its part.

Dominion Energy reported last week on medium-term clean power generation development plans. These plans resulted from the recent Virginia Clean Economy Act that requires net-zero methane and carbon emissions by 2050. The new plans include spending $3.5 billion on developing 2.6 GW of offshore wind and $5.5 billion on roughly 10 GW of onshore wind and solar, significant increases from previous policies.

The Australian Government has established funding to support hydrogen-powered projects. The US$193 million Advancing Hydrogen Fund will be administered by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC). As a priority, CEFC will seek investment in a $70-million grant program aiming to demonstrate the technical and commercial viability of hydrogen production at large-scale using electrolysis. Renewable hydrogen can enable the decarbonization of difficult-to-abate sectors, particularly in transport and manufacturing, while accelerating the contribution of renewable energy across the economy.

Paris-based Neoen will start construction on Australia’s biggest solar farm after winning a power purchase agreement with Queensland state’s renewables company. The company will invest US$366 million in the Western Downs Green Power Hub, with first electricity from the facility expected in the first quarter of 2022. As much as three-quarters of the energy produced by the plant will be taken by CleanCo, making up more than 30 percent of its target for 1 gigawatt of renewable generation by 2025.

6. The Briefs (date of the article in the Peak Oil News is in parentheses)

The worst for oil is over, but the road to recovery will be long and windy, Bloomberg’s Javier Blas tweeted, citing Morgan Stanley analysts. According to them, April was the worst month for oil demand, which from now on will begin to recover, albeit slowly. Oil inventories will continue to rise, however, which suggests it will be a while before oil prices could post any palpable improvement. (5/7)

The glut of natural gas could lead to more canceled LNG exports in the next few months. Global LNG supply was initially expected to rise to 380 million tons in 2020, up 17 tons from a year earlier. However, due to the pandemic, demand will increase by a relatively modest 6 tons, putting the total market at 359 tons for the year. There was an oversupply problem heading into 2020, even before taking the global pandemic and economic downturn into account. Second, the supply overhang will be made worse this year as new additions exceed demand growth. (5/7)

The Saudi-Russian oil price war may be officially over with the new OPEC+ deal. Still, Saudi Arabia has continued to pursue additional market share in Asia aggressively and managed to squeeze share out of its key rivals in the most significant Asian oil importers. Saudi Arabia doubled its crude oil exports to China in April to the highest volumes since at least 2017, exported the most oil to the US since August 2018, and toppled Iraq as India’s top oil supplier last month. (5/7)

Pakistan is likely to run out of petrol and diesel in May and June to meet local demand as the government’s lack of firmness in resolving differences over lockdown compounded the impact of the pandemic-driven supply chain disruption. The problem is due to planning and approval delays at the ministry of petroleum and the non-availability of cargo ships globally. (5/6)

Egyptian billionaire Naguib Sawiris told CNBC on Wednesday that oil could hit $100 per barrel within the next 18 months—a hard pill to swallow with Brent currently trading below $30 per barrel. Sawiris, chairman of one of Egypt’s largest companies, is Egypt’s second-richest man and has a net worth somewhere between $3 billion and $7.5 billion. (5/7)

Algeria – which was already feeling a squeeze on foreign exchange reserves even before oil prices collapsed in early May due to the Saudi-Russian oil price war and the global demand crash in the pandemic – is now taking a drastic action to protect its finances this year. The budget will be slashed by “50 percent” in 2020. (5/5)

Guyana still a go: Oil majors may be slashing spending and deferring development plans across the globe, but they remain committed to developing the newest offshore oil finds in the heart of Latin America. While production in the US shale plays has started to decline in response to the low oil prices, development plans for the significant offshore oil discoveries in Guyana and Suriname remain unchanged. (5/8)

The US oil rig count dropped by 33 to 292, down 513 rigs year-over-year, Baker Hughes reported on Friday. Gas rigs fell by 1 to 80, down from 183 year-over-year. The total number of rigs is now 374, down from 988 last year. It is the fewest number of active rigs since Baker Hughes started to keep records in 1940. (5/9)

North Dakota’s Department of Mineral Resources has established a Bakken Restart Task Force to help with recovery for an industry struggling in the wake of low oil prices and a massive global supply glut. North Dakota’s oil and gas industry added more than 72,000 jobs in the state and was expected to generate $4.9 billion in state revenue from July 1, 2020, through June 30, 2021, or 57 percent of all revenue collected by the state. (5/9)

Texas regulators are relaxing rules about where companies can store oil underground, raising concern among environmentalists about potential groundwater contamination and other dangers. (5/6)

Texas Railroad Commissioner Ryan Sitton said in an interview on Bloomberg TV that the three-member agency wasn’t prepared to vote on curtailing supplies in a process known as “pro-rationing.” His comments likely mark the end of a month-and-a-half-long saga that divided the shale industry over whether regulators should adopt OPEC-style production caps amid a historic collapse in crude prices. (5/5)

In Montana, a federal judge on Friday vacated 287 oil and gas leases on almost 150,000 acres of land, ruling that the Trump administration had improperly issued the leases to energy companies in 2017 and 2018. The judge said the Interior Department’s Bureau of Land Management failed to adequately take into account the environmental impacts of the drilling. District Court Judge Brian Morris found that the officials had not accounted for the drilling’s impact on regional water supplies and the global impact that the increased drilling would have on climate change. (5/5)

Exxon posted its first quarterly loss in more than 30 years. But even as debt mounts and questions arise about peak oil demand, the oil supermajor nevertheless vowed to protect its dividend while also aiming to grow indefinitely into the future. Exxon lost $610 million in the first quarter, down from a profit of $2.4 billion a year earlier. Worse, the period only included a few weeks of oil prices at catastrophically low levels. As a result, the second quarter is bound to lead dramatically worse numbers. (5/5)

Strange drilling restart: US oil prices slumped into negative territory less than a month ago as storage space fills up fast. And yet it appears that some producers are ready to start drilling again the moment WTI reaches a certain level. Interestingly enough, this level is below most companies’ breakeven price. But those companies have debt repayments due so need the cash. One problem is that the moment the oil market gets wind of shale drillers ramping up, prices will slide as fast as they rose because of the fundamentals’ situation. (5/8)

Airlines in stasis: Steven Mnuchin, the US Treasury secretary, said it was “too hard to tell” if the US will loosen international travel restrictions affecting Asia and Europe this year, even as measures limiting domestic economic activity are lifted. US President Donald Trump was “looking about ways to stimulate travel”, Mr. Mnuchin said, but he suggested this effort would initially be limited to travel within the US. The comments, in an interview with Fox Business Network on Monday, compounded a sell-off in airline stocks triggered by news over the weekend that Warren Buffett had sold his entire investment in the sector. (5/5)

UK airlines say they have been told the government will bring in a 14-day quarantine for anyone arriving in the UK from any country apart from the Republic of Ireland in response to the coronavirus pandemic. (5/9)

US total new vehicle sales in April slid by about 50 percent year over year as the coronavirus pandemic limited consumer and corporate purchasing activity during a full month of shelter-in-place measures across the country. New vehicle sales dove to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 8.6 million units from 16.5 million units in April 2019. (5/7)

Car sales in the UK plunged to just 4,321 vehicles in April, down from 161,064 cars sold in the same month last year. The April 2020 new car registrations hit their lowest level since immediately after World War II, in 1946. In this distorted market statistics for April 2020, Tesla Model 3 was the best-selling car in the UK with 658 Model 3s sold. (5/7)

The UK’s 97.3 percent decline in new car sales is in line with similar falls across Europe, with France down 88.8 percent and the Italian market falling 97.5 percent in April. (5/5)

NYC’s peaker plants expensive: In New York City, peak electricity is among the costliest in the country. A new report has found that New Yorkers over the last decade have paid more than $4.5 billion in electricity bills to the private owners of the city’s peaker plants, just to keep those plants online in case they’re needed — even though they only operate between 90 and 500 hours a year. Even at the upper limit, that’s less than three weeks. This all means that the price tag for peak electricity in the Big Apple is 1300 percent higher than the average cost of power in the state. (5/9)

Illinois Basin coal production totaled over 19.2 million tons in the first quarter of 2020, down 7.3 percent from the previous quarter and down 30.7 percent from the year-ago quarter. (5/9)

Aussie coal downer: Financing a thermal coal project in Australia just got a little bit harder after Westpac Banking Corp. said it would exit the sector by 2030, leaving Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. as the last of the country’s big four yet to commit to dropping the most polluting fuel. Australia is the world’s second-biggest thermal coal exporter. Still, it has become increasingly challenging to bring new resources on stream as financial institutions across the globe bow to pressure from shareholders and climate groups to avoid coal investments. (5/4)

Wood vs. steel wind towers: Standing 100 feet tall on the island Bjorko in southwest Sweden, a white wind tower looks indistinguishable from thousands of similar tubes that help generate clean energy all over the world. But inside is another story. The interior of the tower is made of creamy whiteboards, soaring into the air like a hollowed-out tree trunk. It’s a total redesign of the classic steel turbine tower from Swedish company Modvion AB, which says it can cut costs for the renewable power industry and dramatically reduce the sector’s output of greenhouse gases. Steel, the primary material in turbines, is made with fossil fuels and is responsible for emitting about 7 percent of global greenhouse gases every year. (5/6)

Mexico full-stops renewables: The country’s National Energy Control Center announced it would suspend grid connections of new solar and wind farms until further notice earlier this week. The motivation behind the decision was the intermittency of solar and wind power generation, which, according to the state-owned power market operator, could compromise Mexico’s energy security in difficult times. (5/8)

Battery R&D: Researchers at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology have developed a high-capacity lithium-ion battery that is flexible enough to be stretched accordion-like into a honeycomb shape. The resulting stretchable battery showed high storage capacity, superior electrochemical performance, and long-term stability. (5/7)

Transit crash: All around the world, the coronavirus has stopped people from moving — leaving buses, subways, and trains all but empty and passengers apprehensive about any swift return. Ridership has fallen by up to 90 percent on some of the world’s most storied system: the London underground, the Paris Metro, New York’s subways, and Tokyo’s famously packed lines. Experts now fear the lockdowns will leave networks struggling with twin problems: how to recover from a huge revenue hole and persuade riders that it’s safe to come back to one of the cornerstones of city life. It may be years before a new normal is established. (5/9)

The pandemic-induced job market collapse robs President Trump of his chief argument for re-election. It will fuel his drive to quickly “reopen” the US economy, even as solid majorities of Americans are reluctant to return to public life. (5/9)

Pandemic repatriation: India is working with some Arab Gulf states to repatriate hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers stranded by the coronavirus pandemic, in what could become one of the largest emergency evacuations in decades. Starting in a few days, India plans to begin deploying military ships and its national airline for the effort, while Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates use civilian airliners. The first wave of repatriations could bring 192,000 Indians home by mid-June. (5/5)