Editors: Tom Whipple, Steve Andrews

Quotes of the Week

“It’s a make-or-break moment. This may be the greatest global crisis we’ve faced in the postwar period.”

Maury Obstfeld, former IMF chief economist

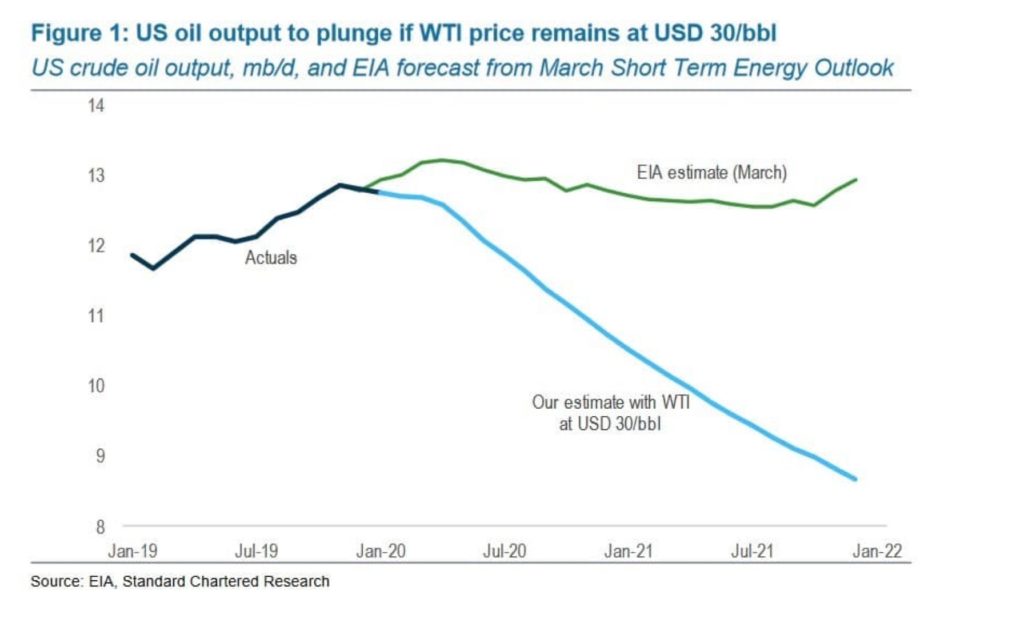

“Everything depends on price. Standard Chartered estimates that the US could lose 4 million b/d by the end of next year if oil prices remain at $30 per barrel. Either way, US oil production has peaked, and it will be difficult to climb back to these levels ever again, given how much capital markets have soured on the industry. The EIA said that the US will once again become a net petroleum importer later this year, ending a brief spell during which the US was a net exporter.”

OilPrice.com, editorial

Graphic of the Week

| Contents 1. Energy prices and production 2. Geopolitical instability 3. Climate change 4. The global economy and trade wars 5. Renewables and new technologies 6. Briefs |

1. Energy prices and production

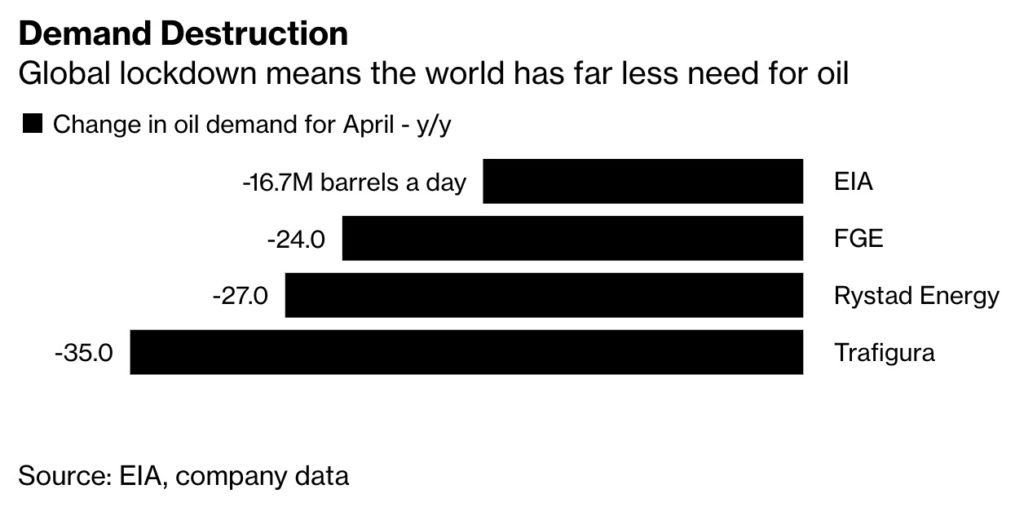

It was a volatile week as the world’s major oil producers struggled to find a way to raise prices from ruinous levels as the global consumption of oil sank by about a third from pre-virus levels. Reports of new highs in the virus infection count and death toll continue to pour in from all over the world, suggesting that the demand for fossil fuels still has a way to fall.

OPEC, Russia, and other oil producing nations finally agreed on Sunday afternoon to cut output by 9.7 million b/d for May-June after four days of marathon talks. OPEC+ has said it wanted producers outside the group, such as the United States, Canada, Brazil and Norway, to cut a further 5 percent or 5 million b/d. Mexican officials say they will cut production by 100,000 b/d with the US responsible for cutting the remaining 300,000. The fate of this additional 5 million b/d cut still has not been revealed. The 10 million b/d cut is about a third of the current oversupply and for now seems unlikely to move oil prices higher unless there is a major change in the course of the pandemic and efforts to mitigate it.

The week before last, the world’s oil markets were in a mess. Oil prices, which were above $60 a barrel in January had fallen to circa $25, and it had become apparent that around a third of the world’s demand for oil had melted away as the coronavirus forced the lockdown of most of the world’s largest consumers. Russia and Saudi were in a market war, and the Saudis were trying to flood the oil market with cheap crude. A glut of crude oil was forming that soon would overtake the world’s ability to store oil, and producers would be forced to shut down production, damaging the long-term output of many wells.

Late in the week before last, President Trump tweeted that Russia and the Saudis were close to an agreement to cut world oil production by 10 to 15 million b/d. It later was revealed that the President had threatened Moscow and Riyadh with US tariffs on their oil exports if they did not settle their production war. At first, the markets were skeptical that a production cut of this magnitude was really in the offing and then whether it could come soon enough and be large enough to overcome the massive overproduction that would soon swamp storage facilities.

By Tuesday, it appeared that Russia and the Saudis were serious about cutting production, as the low oil prices were destroying their national budgets. The deal which was made via teleconference was to have Moscow and Riyadh each cut their output by 4 million b/d. Other members of OPEC+ would absorb another 2 million b/d cut, bringing the cut to 10 million.

Then there was the issue of other large non-OPEC producers sharing the burden. Washington claimed it did not have to make any precise cuts, as high-cost US shale oil production was falling like a brick and would likely be a million or two b/d lower by the end of the year. This seemed to satisfy Moscow, but others were griping that the US should shut-in some of its Gulf of Mexico production. Unlike most of the world where the government owns and controls oil production, US oil companies are not as yet controlled by the government and except for licensing drilling of federal land, Washington has no say in production decisions which are controlled by the market.

West Texas Intermediate crude slid more than 9 percent Thursday afternoon settling below $23 a barrel, on speculation that any cut would fail to offset a glut that keeps swelling as the pandemic spreads. Markets were closed on Friday.

After the OPEC+ teleconference on Thursday, the G20 energy ministers had a teleconference on Friday, which included the US. This conference was to settle the remaining 5 million b/d cut. The G-20 said it would take “all the necessary measures” to maintain a balance between oil producers and consumers, but it did not commit specific steps on production cuts. The communique was watered down from earlier drafts, notably removing language that said the group would do “whatever it takes” to ensure that the energy sector is contributing to the global recovery from the pandemic.

At this point, the problem of Mexico’s production arose. The Saudis were insistent that Mexico’s fair share of a production cut would be 23 percent or 400,000 b/d out of Mexico’s daily production of 1.6 million b/d. Mexico’s Energy Minister Nahle didn’t budge from her insistence that the country could only cut output by 100,000 b/d, 300,000 less than its “fair share” of 23 percent reductions by everyone in the OPEC+ group.

The Mexican government refused to make such a large cut. For years Mexico had been hedging much of its crude production on the futures markets to guard its budget against sudden oil price drops. Some sources say that Mexico City had spent $1 billion on the hedges and that they could now get $50 a barrel for their hedged oil rather than the market price that was in the $20s for their grades.

On Friday morning, Mexican President Obrador said he had resolved the matter in a phone call with President Trump. The US would make an additional 250,000 b/d of cuts on Mexico’s behalf. Trump later suggested output cuts American producers have only started making to weather the price crash could be counted toward Mexico’s share of the pact.

Russian energy minister Alexander Novak said Friday that OPEC+ expects producers outside the group to cut another 5 million b/d of crude production in May and June. “We think that in addition to the 10 million b/d that OPEC+ will cut, there will be another 5 million b/d cut by countries that are not included in OPEC+, so in total the cut in May and June will be 15 million b/d.”

The shale boom that turned the US into the world’s largest oil producer is unraveling fast. Last week, the country’s production fell by 600,000 b/d from a near-record 13 million as shale drillers idle rigs in the Permian Basin and elsewhere in the country. Energy Secretary Brouillette, in opening remarks at the G-20 meeting, said he predicted a decline of nearly 2 million b/d in US output by the end of this year.

US crude inventories saw their largest-ever weekly build last week as refinery demand cratered amid a historic collapse in product demand. The bulk of the build was at Cushing, Oklahoma, where stocks climbed 6.42 million barrels to 49.24 million barrels. The build was the largest-ever on record at Cushing and put tank levels there at an estimated 62 percent of working capacity.

US gasoline demand has collapsed with sales at retail stations down 46.6 percent from a year earlier in the last week of March. The loss of consumption in the US echoes that of Spain and Italy, where demand for gasoline was down about 85 percent.

Natural gas production in the US is expected to drop by the fastest pace ever in 2021 as drillers slash spending in response to the glut. Gas output is poised to fall by 4.4 percent to average 94.49 billion cubic feet a day next year, the US Energy Information Administration said in its Short-Term Energy Outlook last week. That would be the biggest annual retreat in data going back to 1998.

Exxon Mobil Corp. more than doubled the budget cuts announced by any other shale company last week. In all, nearly three dozen shale drillers have slashed more than $27 billion from their budgets in less than a month. Exxon, alone, said it would cut $10 billion in spending, a 30 percent reduction. ExxonMobil saw its credit rating downgraded by Moody’s on Thursday from Aaa to Aa1, with a Negative outlook.

US crude oil pipeline giant Plains All American said it would cut its spending by almost 50 percent, and Oklahoma oil producer Continental Resources aims to reduce its production volumes by 30 percent in April and May.

2. Geopolitical instability

Iran’s president said last week that “low-risk” economic activities would resume on April 11th in provinces outside the capital affected by the coronavirus. “Low risk” activities are to resume in Tehran on April 18th. Authorities are concerned that measures to limit public life to contain the virus could wreck an economy already battered by US sanctions. Rouhani did not spell out what he meant by low-risk activity but said the ban on “high-risk activities” – schools, universities and various social activities, sports and religious events would be extended to April 18th.

Many businesses took the announcement early last week as a green light to start returning to normal life, with Tehran’s roads and metro stations packed last Monday. Iran has been one of the countries hit hardest by the pandemic, recording about 70,000 confirmed cases and more than 4,000 deaths.

Tehran unveiled a package of state-backed loans to support poorer people and boost consumer spending as the government prepares to ease some of the work restrictions it imposed to contain coronavirus. President Hassan Rouhani said the measures would include guaranteeing a bank credit of $61 to 23 million families – most of the population.

Their deteriorating economic situation has forced the Saudis to announce a nationwide ceasefire in the Yemen. The Iran-aligned Houthi movement, which controls the capital Sanaa and most big urban centers, has yet to announce whether it will follow suit in what would be the first major breakthrough in peace efforts since late 2018. The five-year-old war has killed more than 100,000 people and pushed millions to the brink of famine.

Saudi Arabia’s sovereign-wealth fund has amassed stakes worth roughly $1 billion in four major European oil companies, buying assets it perceives as undervalued in a market depressed by the low oil prices.

The stakes in Equinor, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, and Eni were all bought by the Saudi’s Public Investment Fund in recent weeks. The investments mark a significant tactical shift for the roughly $300 billion Public Investment Fund, tasked by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman with diversifying the country’s economy away from oil by largely investing in companies and industries untethered to hydrocarbons.

An oil export terminal blockade that led to the shutdown of fields and refineries has so far cost Libya close to $4 billion, the National Oil Corporation said in a statement this week. Production now is down to below 90,000 b/d.

Political instability continues in Iraq as Iraq’s President Bahram Saleh named intelligence chief Mustafa al-Kadhimi as the new prime minister designate, after Adnan al-Zurfi withdrew his candidacy amid political opposition to his nomination. Kadhimi now has 30 days to form a government and get parliament’s vote of confidence. Zurfi is the second candidate to withdraw from the prime minister race after Mohammad Allawi failed to win parliament’s vote of confidence for his cabinet.

A sign that Washington has had enough of the endless political maneuverings in Baghdad came when it only extended its latest waiver allowing Iraq to continue importing electricity and natural gas from Iran for 30 days. Without the imported energy, Iraq would have a hard time keeping the lights on.

Several rockets were fired last week at a residential district in southern Iraq, where many foreign oil firms have their headquarters and where oil workers live. The rockets did not cause damage or injure anyone or disrupt oil production. The district, near Iraq’s major city of Basra, was largely empty because many foreign oil companies had evacuated their personnel due to the coronavirus pandemic. Rocket fire is not uncommon in Iraq, where the US embassy in Baghdad has been targeted a few times this year by Iran-backed paramilitary factions.

Gasoline shortages in Venezuela worsened after US officials told foreign firms to only sell diesel to Caracas. Refineries in the country are falling apart and can only process about 10 percent of capacity. In the latest round of calls in early March between US officials and oil firms, they repeated the ban, despite worsening humanitarian conditions in the country. A handful of foreign companies – including Russia’s Rosneft, Spain’s Repsol, Italy’s Eni, and India’s Reliance – continued to supply fuels to PDVSA under swap arrangements for Venezuelan crude oil, which was allowed by the US Treasury.

The Trump administration continues to tighten the noose around the Maduro regime. Venezuela is already reeling from a years-long economic disaster that has slashed its crude oil production in recent years. This year, the country found itself with two new crises to manage—the coronavirus pandemic and the tumbling and highly volatile oil market with oil prices so low that they can’t cover the costs of pumping Venezuela’s heavy crude out of the ground. The country is also faced with the return of tens of thousands of Venezuelans who fled to Columbia due to food shortages. As the coronavirus sweeps Columbia, the Venezuelan refugees are no longer welcome.

The US Treasury Department again extended for three months a waiver preventing creditors of Venezuela’s PDVSA from taking control of US refiner Citgo as a result of missed payments on its 2020 bonds. The waiver, set to expire on April 22, was extended until July 22. Another waiver, allowing Chevron and four US oil services companies to continue to work in Venezuela with state oil company PDVSA, is still set to expire on April 22. The State Department will not comment on whether the Chevron waiver would be extended. Some analysts claim that Venezuela’s oil output, which averaged 650,000 b/d in March, could fall below 300,000 b/d if the Chevron waiver is not renewed.

3. Climate change

With much of the world closed down, gasoline consumption down 50 percent, and electric power consumption much lower, blue skies are appearing all over the world. The most dramatic are pictures from northern India showing the snow-capped Himalayas – a sight which has not been seen for decades.

Whether we shall still see blue skies once the world’s economy returns to “normal” is an open question. Many are lamenting that we are entering a period of economic hardships in which climate change will be lost in the struggle to regain economic growth. Others are hopeful that even a short period of pre-industrial air quality will trigger more enthusiasm for a time with much lower consumption of fossil fuels.

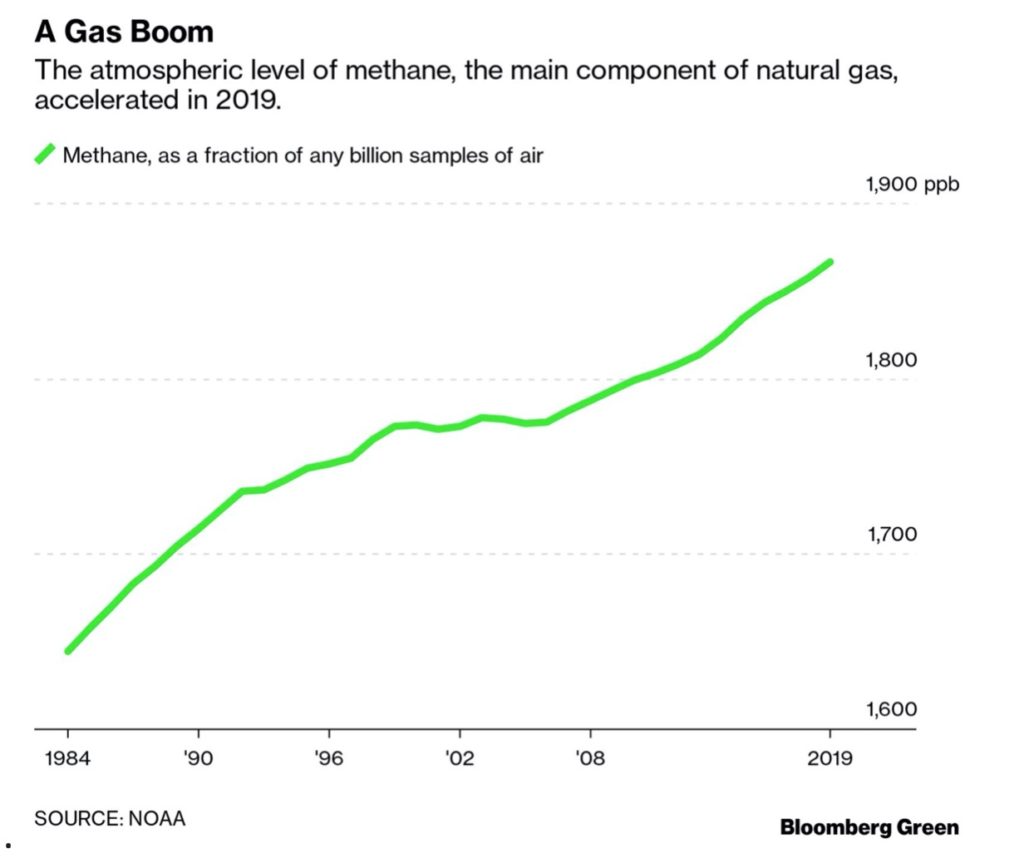

Airborne methane levels rose markedly last year, according to a preliminary estimate published today by the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The results show a dramatic leap in the concentration of the second-most-powerful greenhouse gas, which is emitted from both industrial and natural sources. Methane is about 25 times more potent a heat-trapping gas than its nearest competitor—carbon dioxide—when extrapolated over a century.

“Last year’s jump in methane is one of the biggest we’ve seen over the past twenty years,” said Rob Jackson, professor of Earth system science at Stanford. “It’s too early to tell why but increases from both agriculture and natural gas use are likely. Virtually every contributor to the global methane problem may play a role, from the oil-and-gas industry to human agriculture to wetlands changing with the climate.

4. The global economy and trade wars

With many national economies all but shutting down to contain the coronavirus, prices on everything from oil and copper to hotel rooms are tumbling. The falling prices are pushing the world into a dangerous deflation for the first time in decades. This situation is troubling because it could lengthen what may be the deepest recession since the 1930s.

Ebbing pricing power makes it harder for companies that piled on debt in good times to meet their obligations. This could prompt them to make additional cuts in payrolls and investment or even default on their debts and go bankrupt. A widespread deflationary price decline can be bad for the whole economy. Households hold off buying in anticipation of ever-lower prices, and companies postpone investments because they see limited profit opportunities.

Down the road, there’s a chance that the massive outpouring of government debt to pay for the fight against the virus could spawn a build-up in price pressures. “It’s possible that the response to economic shutdown over the longer term could have an inflationary consequence,” former New York Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Bill Dudley. “But in the near term, it’s very definitely on the disinflationary/deflationary side.”

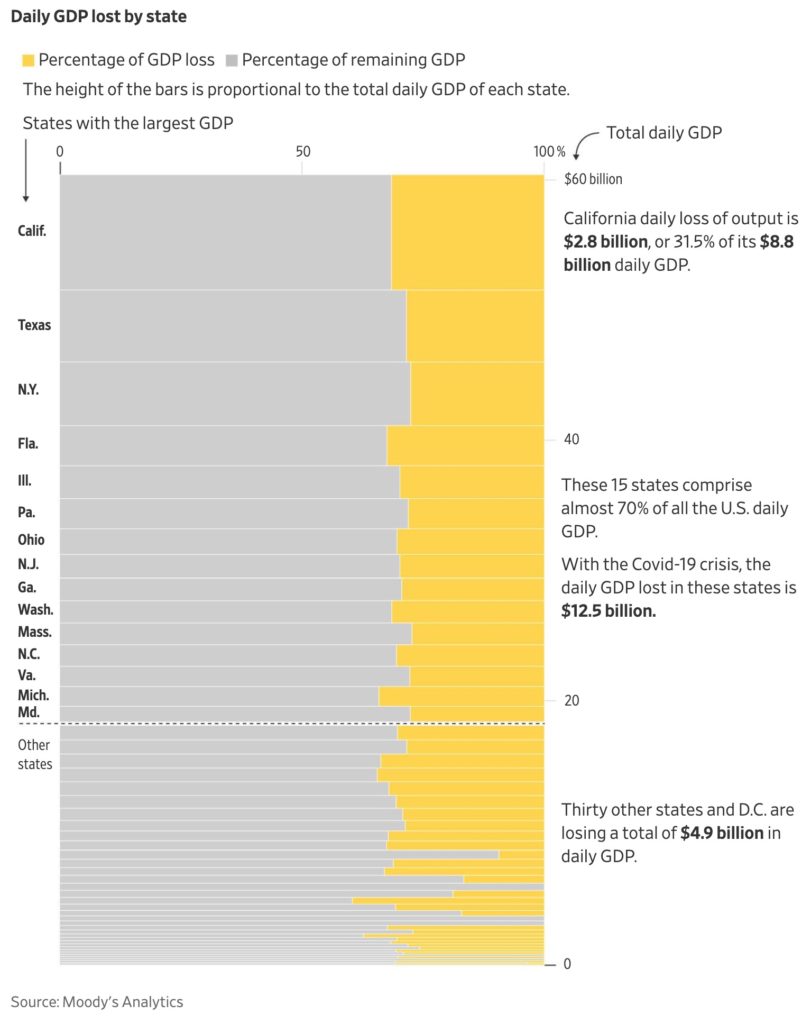

At least one-quarter of the US economy has suddenly gone idle amid the pandemic. An analysis conducted for The Wall Street Journal shows an unprecedented shutdown of commerce that economists say has never occurred on such a vast scale. While 8 in 10 US counties are under lockdown orders, according to Moody’s, they represent nearly 96 percent of national output.

Most economists expect output to pick up this summer or in the fall as states reopen and virus cases drop. But the magnitude of the drop in daily production—however long it lasts—is staggering. Annual output fell 26 percent between 1929 and 1933, during the Great Depression, Commerce Department data show. Quarterly production fell almost 4 percent between late 2007 and mid-2009, the last recession.

One economist said, “This is a natural disaster, there’s nothing in the Great Depression that is analogous to what we’re experiencing now.” Most analysis almost certainly underestimates the total hit because it looks only at lost output caused by the abrupt closure of businesses to date. It doesn’t consider how much production will be lost due to additional demand-side drops from higher unemployment and the loss of household wealth on household and business spending.

The situation in China is still unclear. The government says that only a few new cases of the virus are turning up, and most of these can be traced to recent foreign travel. The lockdown of Wuhan, the epicenter of the virus, ended on Wednesday. However, severe travel restrictions are still in place, including a variety of tests and quarantines for anyone who has been in Wuhan.

While many businesses have reopened, many were bankrupted by the epidemic and lengthy shutdown. Beijing’s ability to export has been severely reduced as container shipping is a mess, and most importers of China’s exports are shut down. Anecdotal evidence says that Chinese consumers are reluctant to purchase much beyond necessities until they are sure all is well.

This leaves the government with its old standby, government-financed public works, to get people back on the job and the economy moving. With restrictions on the free movement of labor still in place, with a patchwork of policies and regulations, it will take many months before the Chinese economy recovers its former vigor.

5. Renewables and new technologies

With much of the world’s economy shut down, there has been little news about renewables and new technologies of late. Much pessimism is being expressed these days about renewable forms of energy as investment is dropping rapidly. Numerous commentators have said they don’t see much of a future for electric cars in the short term as gasoline is now so cheap. Countering this argument is a report from China, the only place where a Tesla factory is still operating, that set a sales record last month of 10,000 vehicles being sold despite the total sales of vehicles in China plunging 41 percent year over year.

As the demand for electricity falls to record lows and revenues drop, those companies that have fuel-free renewables, are seeing an increase in the share of power generated by wind and sun.

The World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency will provide funding for six new solar power plants in Upper Egypt, one of the largest such installations in Africa. The total investment of $52.35 million will be issued in the form of guarantees to Norwegian photovoltaics firm Scatec Solar. It will be used for the operation and maintenance of the new plants.

6. The Briefs (date of the article in the Peak Oil News is in parentheses)

In the North Sea, oil and gas production became viable due to the 1973 oil crisis. The current crisis could be the final blow to an industry that was already struggling to survive. Energy companies need prices above $40 to maintain profitability. A window of $60-$70 would be “comfortable,” while $40-$50 puts many projects in the “risk zone.” On average globally, projects are sanctioned at a breakeven oil price of $35 per barrel. Currently, Brent Crude is trading for approximately $25 and it could slide even further. The number of workers that operate oil and gas platforms under normal circumstances stands at about 11,500. But that has already fallen to 7,000 within just a couple of weeks, (4/6)

In India, oil demand in the world’s third-biggest consumer has collapsed by as much as 70 percent as the nation endures the planet’s largest national lockdown. The estimate for the current demand loss is a stark reminder of the challenge facing oil producers as they haggle over a deal to cut supply and prop up the global energy industry. (4/9)

Australia will increase its oil stock through an agreement with the US to help support the global market, following a video conference with G-20 energy ministers. (4/11)

Fuel demand in Argentina, under lockdown since March 20, is tumbling, and YPF is running out of storage for its crude oil, so the state energy firm closed 50 percent of its producing wells in the Loma Campana development. Other companies, such as Vista Oil & Gas, have also reduced their production. (4/11)

Airplane emissions fell by almost a third last month as the coronavirus lockdown grounded flights around the world, a drop in emissions equivalent of taking about 6 million cars off the road. The number of scheduled flights in the last week of March was half that of the same period a year ago. (4/11)

Mexican standoff? Outside of Saudi Arabia and Russia, most oil producers are racing to deal with the historic oil price collapse by cutting back spending and in some cases production. But Mexico’s national oil company is acting like the crash never happened. PEMEX aims to nearly double drilling to 423 wells this year and accelerate development of 15 recent discoveries, even though experts say many are unprofitable at current prices. (4/9)

The US oil rig count dropped sharply, down 58 rigs to a total of 504, Baker Hughes reported. That is well below last year’s count of 833 oil rigs. Gas rigs decreased by 4 to 96, down from 189 last year at this time. (4/11)

In Alaska, UK-based oil exploration firm Pantheon Resources believes it has a 1.8-billion-barrel oil discovery after evaluating an old exploration well. Despite low oil prices, Pantheon believes the discovery could become commercial and viable at oil prices around $30 per barrel. The discovery is south of Prudhoe Bay and along the Dalton Highway and Trans-Alaska Pipeline System corridor. The proximity to Dalton Highway helps. The discovery, named Talitha, could be able to produce as much as 500 million barrels of oil, while peak oil production could be almost 90,000 b/d.

Rigs could drop 65 percent: The American oil and gas industry is stepping heavily on the brake pedal and is reducing drilling at record speed, Rystad Energy research shows, putting the horizontal oil rig count on track to fall by about 65 percent from mid-March levels. (4/8)

ExxonMobil is slashing this year’s capital spending plans by $10 billion and will cut cash operating expenses by 15 percent as it seeks to preserve its dividend in the face of the crude price collapse sparked by coronavirus. Capital investment this year will be $23 billion, down from the previously announced $33 billion. The biggest cuts will be in the Permian Basin, the heart of the US shale boom, where Exxon’s drilling will slow – the second time in two months that the company has lowered its output projections for the area. (4/8)

EIA finally cuts big: The US EIA cut its 2020 oil production forecast by more than 1 million barrels a day, as collapsing crude prices and plummeting demand threaten to shutter production in the country’s biggest fields. Production is expected to average 11.76 million barrels a day through December, down from a previous forecast of 12.99 million barrels, the EIA said. The agency also trimmed its 2021 output expectations by 1.6 million barrels a day to just over 11 million daily barrels. (4/8)

Oil industry giants in the US aren’t likely to get a bailout because, as Trump has made relatively clear of late, it’s a free-market question. The new rules of the game favor clean energy because not even a bailout–and certainly not a new OPEC deal–can save the industry from the new normal. The US shale patch, despite soaring production, was already traversing the beginning of the end before the coronavirus decimated demand. (4/10)

Some old-guard Texas oil drillers are urging state regulators to clamp down on crude production to halt a price collapse more severe than any of them have ever lived through. The largest US oil-producing state hasn’t restricted crude production in almost 50 years, but a growing chorus of explorers and related industries are advocating just such a move. The Texas Railroad Commission that has overseen the state’s industry for more than a century is scheduled to discuss so-called pro-rationing on April 14. (4/7)

Oil asks for Fed aid: Occidental Petroleum is opposing a Texas-wide mandated production cut, but through a letter to Congress it is asking the US Administration for federal financial assistance for the US oil industry which can’t make any money at $30 oil. (4/10)

Dialing down refineries: Limited storage for refined products has forced BP to cut the refinery rates at its three largest refineries in the US to 80-85 percent as fuel demand is crumbling amid lockdowns and stay-at-home orders. (4/10)

The American ethanol industry is cutting production like never before as coronavirus lockdowns keep drivers off the roads, crushing demand for fuel. Output of corn-based biofuel plunged by a record 20 percent to an average daily rate of 672,000 barrels. After the virus helped drive down oil prices amid a dispute between Russia and Saudi Arabia over production levels, ethanol producers can no longer profitably make the fuel. (4/9)

The world’s airlines, no longer operating a globe-spanning choreography of flights, are consumed with new work: navigating government bailout offers, negotiating with unions, finding places to park idle planes and scrounging for business like flying cargo and repatriating marooned travelers. Expansion plans aren’t just on hold amid the coronavirus crisis; executives are plotting major retrenchments they expect to last for months. (4/6)

Air travel down 95 percent: The number of Americans getting on airplanes has sunk to a level not seen in more than 60 years as people shelter in their homes to avoid catching or spreading the new coronavirus. The TSA screened fewer than 100,000 people on Tuesday, a drop of 95 percent from a year ago. Historical daily numbers only go back so far, but the nation averaged 97,000 passengers a day in 1954. (4/9)

Maritime shipping down: Maritime data provider Alphaliner said in a report Wednesday that shipping lines have withdrawn vessels with capacity totaling about 3 million containers in efforts to conserve cash and maintain freight rates. (4/9)

Wood power closes down: Out in the Piney Woods of East Texas, on the outskirts of a town that’s supported a thriving logging industry for more than a century, there’s a hulking power plant for sale. But it hasn’t run since 2015 and never turned a profit. The most likely outcome is getting bought, dismantled, and hauled off to some place where producing electricity from burning wood makes economic sense; the numbers don’t work here anymore. (4/8)

Saudi nuke construction: Saudi Arabia has nearly completed construction of its first nuclear reactor, sparking fears about the country’s quest for nuclear power. New satellite images show construction on the building site has made significant process over the past three months. (4/9)

Food shipments troubled: Chokepoints in seaside ports are just the latest example of how the virus is snarling food production and distribution across the globe. Trucking bottlenecks, sick plant workers, export bans and panic buying have all contributed to why shoppers are seeing empty grocery store shelves, even amid ample supplies. (4/10)

The French economy shrank the most since World War II in the first quarter, and the outlook for the rest of the year is souring significantly amid the confinement to limit the spread of the coronavirus, according to the Bank of France. Such a GDP drop from one quarter to the next would be comparable only to the 5.3 percent recorded around the strikes of May 1968. The Bank of France survey also showed that factories are running at just 56 percent of capacity — a record low — down from 78 percent in February. That loss of activity means that for every two weeks of confinement, 2020 GDP will be 1.5 percent lower. (9/8)

Putin steps back: When it comes to containing coronavirus, the Kremlin has a solid plan: Russia’s president Vladimir Putin promises everyone a month-long holiday; regional governors have to come up with painful restriction measures to then keep people in their homes. As Putin distances himself from lockdown measures that look set to plunge the country into a sharp recession, regional governors and local officials have been thrust into the leadership vacuum. None more so than Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin, who has emerged as the public figurehead of Russia’s initiatives against COVID-19, overshadowing other officials and shaking up the country’s well-established system of top-down government. (4/6)

A small Chinese city on the border with Russia is mounting an increasingly urgent defense against a surge of new coronavirus cases even as crowds return to restaurants and shops in much of the rest of the country. Suifenhe in China’s far northeastern Heilongjiang province has seen an influx of Chinese people returning home, many infected with the virus, travelling by road from the Russian far eastern city of Vladivostok after flying there from Moscow. (4/10)

Japan’s lagging: Commuters heading to work packed into trains in the Japanese capital on Wednesday, the first day of a state of emergency aimed at containing the coronavirus outbreak, with some expressing confusion over how best to restrict their movements. The scenes across central Tokyo contrasted with deserted streets and tough lockdowns elsewhere in the world because Japanese authorities have no penalties, in most cases, with which to enforce calls for people to stay home and businesses to shut. (4/8)

Hot weather virus blues: The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, in a public report sent to the White House, has said, in effect: Don’t get your hopes up that the coronavirus pandemic will fade in hot weather, as some viral diseases do. (4/9)