Editors: Tom Whipple, Steve Andrews

Commentary from your Editors:

During these times of tremendous turmoil, it may seem a little irrelevant to change the name of an energy newsletter and then bother to explain why. We acknowledge the overwhelming concerns of the day, knowing that your focus is elsewhere. We hope this missive finds you all in good health and reasonable spirits.

The name change—from Peak Oil Review to The Energy Bulletin—does not mean that your editors, who started the Peak Oil Review in January of 2006, will stop following the peak oil story. Far from it. Instead, we are merely acknowledging that factors impacting the trajectory of world oil production are interacting in ways more complicated than when we began following the story during the 1980s and writing about in 2006. What follows are some observations on both past and present, and possibly future, world oil production.

Reflections on the Peak Oil Story—Never Say Never

“I wouldn’t be surprised if world oil production peaked by 2010 but I would be shocked if it didn’t peak by 2015.” So said a very knowledgeable Denver-based energy analyst, advisor and banker in 2005. By 2014, his views had changed dramatically, thanks to the tight-oil revolution (referred to below as shale oil): “we won’t peak until at least 2020 and maybe later.” We tended to agree with that expert’s perspective, both in 2005 and as it had evolved by 2014.

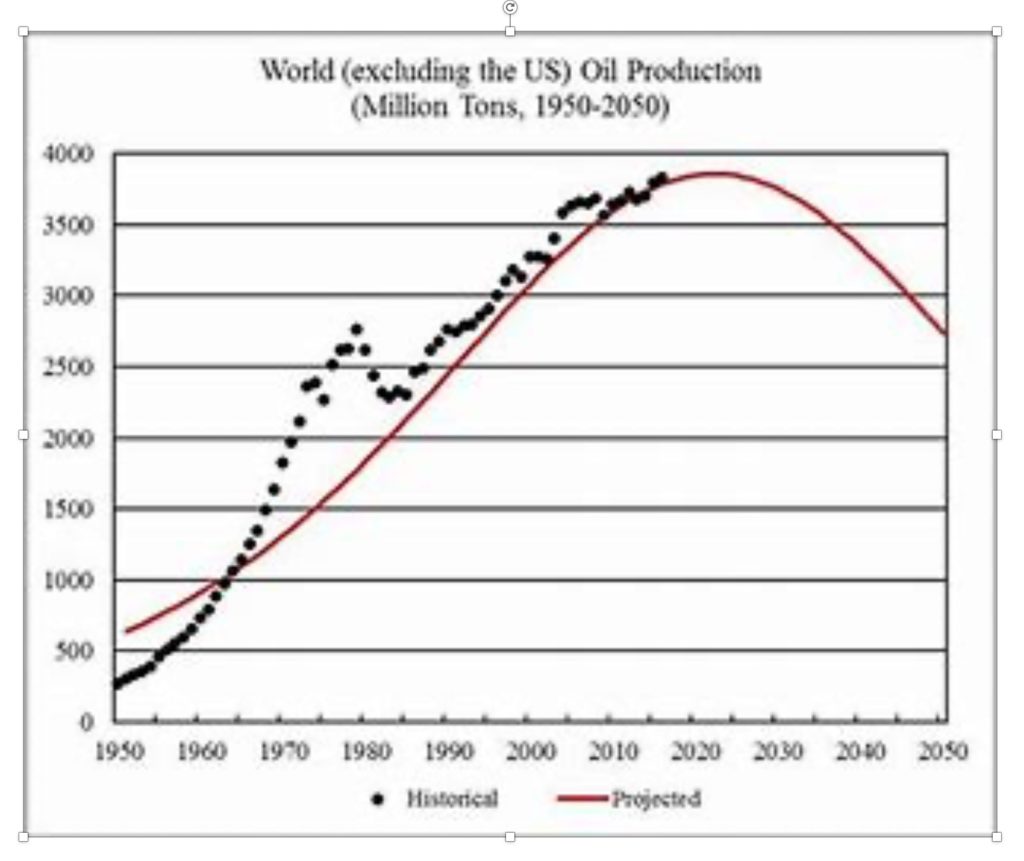

From its inception, the peak oil story tended to focus on geologic limits. In its purist form, the theory is that when roughly half of the world’s discovered oil has been produced, production increases will slow, then plateau and eventually decline during subsequent years. The backside of the bell-shaped production curve might look quite different from the front side; in particular, it might decline more sharply for macroeconomic reasons.

Other key elements of the storyline, back in 2005, when ASPO-USA convened its first peak oil conference in Denver, included the following drivers:

1. Oil discoveries had peaked earlier and were in long-term decline.

2. Peak oil production would lag some decades behind peak oil discoveries.

3. Much of the cheapest and easiest-to-extract oil had been or was being produced, shifting reliance to ever-more-expensive oil.

4. Recovery technologies, including secondary and tertiary, were relatively well developed and deployed.

5. The unconventional oils would be more expensive and wouldn’t scale up to have a big impact; they would merely cushion the rate of decline from conventional oil production.

6. Shifting from oil and gas to renewable energy alternatives would be costly and would not scale sufficiently quickly to have a significant impact.

As a result of the above and other factors, world oil production was expected to peak “soon”. Typical estimates ranged from 2005 to 2015. During 2005, the US EIA’s first Reference Case estimated peak world production would occur in 2016, but most of their scenarios ranged into the 2020s and beyond. A few optimists—notably Cambridge Energy Research Associates—figured a peak would occur during the late 2020s and be followed by a decade-long plateau.

Some of the fundamental concerns listed above were on target. Yes, discoveries were, and still are, declining. Yes, outside of the Middle East, cheap oil was disappearing. Yes, the shift towards more unconventional oil—heavy oil, oil sands and eventually shale oil—was more expensive.

But did world oil production slow as projected by the peak oil community? No. In fact, hell no.

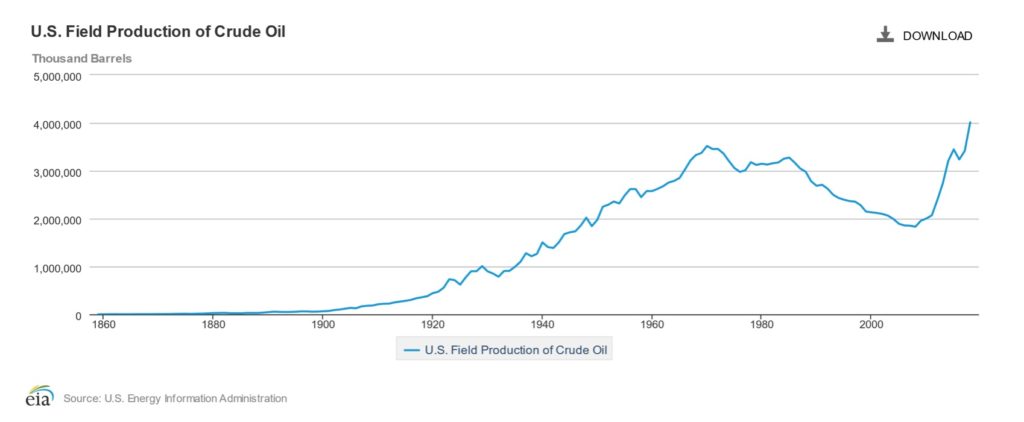

The US-driven shale oil boom led to the fasted growth in production in any one nation during the shortest period of time in the history of all oil-producing countries. US production of crude oil, which had previously peaked at 9.6 million b/d in 1970, bottomed at 5 million in 2005, then slowly increased to 5.7 million in 2011 and then rocketed to 12.2 million last year. That’s a 6.5 million b/d increase over eight years.

The shale oil revolution wasn’t based on new discoveries; the Bakken shale oil formation had been discovered during the 1950s but was too costly to produce. It was the combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracking—pioneered by George Mitchell (Mitchell Energy)—that eventually lead to the unlocking of natural gas from the Barnett shale formation in Texas. The Bakken oil field in North Dakota followed this and then other shale gas and oil formations around the country.

The peak oil community missed four key factors. First, we underestimated the ability of technology to unlock the challenging shale formations. Second, we underestimated the industry’s ability to rapidly scale up production from shale. Third, we underestimated the oil industry’s ability to expand production to take advantage of higher prices; macroeconomics mattered. Finally, we underestimated the willingness of Wall Street to underwrite the highly questionable financial returns from most shale oil projects. (To repeat a famous oil-related title from The Economist magazine in November 1999, “We wuz wrong…”)

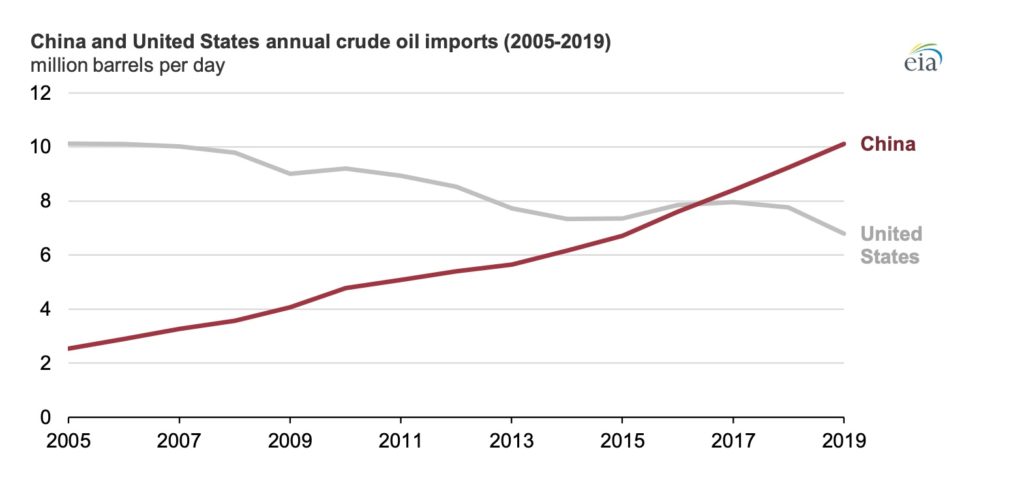

At the world level, the combination of more investment in off-shore oil drilling, the opening up of small new finds, the development of a broader range of resources at higher oil prices, plus the boom in shale oil and tar sands in North America, continued to lift world oil supply to meet growing demand. It was a welcome reprieve to the oil industry and to oil-thirsty consumers. And that reprieve—coupled with a new discussion about “peak demand for oil”—virtually buried the discussion about peak oil that itself had grown steadily between and 2000 and 2010.

Yet in all likelihood, all the boom did was push out, by a decade or possibly two, the peaking of world oil production. Several of the fundamental drivers of the peak oil theory remain alive and well in today’s world of petroleum production.

Consider the following:

–Only a dozen or so nations show potential to continue growing crude oil production for a while longer: the US, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Iraq, Iran, Kuwait, the U.A.E., Kazakhstan, Oman, and Guyana, plus an offshore-Africa basin or two. Russia—whose production has inched up by an average of just over 100,000 bd/yr for the last nine years—does not appear to have any remaining step-function increases in its near future, though it may inch up for a few more years. While Russia has several potentially large but delayed projects pending, the relentless depletion of existing fields will make it difficult for Russia to record significant net increases

–Over 25 nations appear to be past the peak in their oil production. The list ranges from current and former top-10 world oil producers like China, Mexico, Norway and the United Kingdom, to mid-level producers like Angola, Indonesia, Algeria, India (on a plateau), Azerbaijan, Argentina, Egypt, Australia and Malaysia, to another dozen smaller producers like Denmark, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Vietnam.

–At any one time, up to 10 oil producers face volatile production numbers due to either internal strife, corruption, theft, civil war, or conflict with neighbors. The current list includes Venezuela, Nigeria, Colombia, Libya, Syria, Yemen, Sudan and South Sudan. Their level of future production could grow, or it could continue to stagnate and possibly further decline.

–The shale oil industry in the US, the driver for the world-class increase in U.S. oil production during the past decade, was already in a world-class financial bind at the start of the year. With the now-elevated financial turmoil in the financial and oil markets, thanks to the coronavirus as well as the oil market share wars between Saudi Arabia and Russia, the shale sector of the U.S. oil industry is almost certainly going to experience a second round of crippling bankruptcies.

A critical difference between now and the previous wave of bankruptcies: there was still several years’ worth of drilling sites within the “sweet spots” of known shale plays, and technology improvements were still in the pipeline. Neither of those advantages are likely to be significant factors during a future recovery.

–The shale oil industry has not managed to increase substantially beyond North America. Development of Argentina’s prolific Vaca Muerta play may be held back by volatile economics and national politics. In England and Europe, shale drillers face both financial challenges and insurmountable political barriers. In China, the potential from shale seems difficult to tap.

While the past teaches us never to say never, the potential for worldwide growth in shale production looks limited. And, in the larger scheme of things, how much shale oil will the industry bring to the ultimately produced production total? 50 billion barrels? 150 billion barrels? Out of a total, what, several trillion barrels? From the historical lens of the year 2075, the boom in shale may eventually be viewed as the Last Hurrah. But never say never….

–On the plus side, we note the move towards electric vehicles and the infrastructure needed to support it. Additionally, we note the desire expressed by organizations and governments to electrify some end-uses (e.g., space heating, water heating, etc.) currently met with fossil fuels. To make any sense, this change will involve a massive upgrade of energy efficiency. These substantial investments may be challenging to implement soon, given the extraordinary debt currently being taken on by a number of governments worldwide to keep their economies from collapsing.

Unless there is a massive turn, and soon, towards 1) a war-time commitment to fully upgrading the energy efficiency of existing buildings and 2) a war-time commitment to expanding renewables (coupled with storage), we see the pace of future electrification of many fossil-fuel-powered energy end uses falling short of the pace needed to replace eventual dwindling oil supplies. Then again, the impetus for change from the organizations and people pushing meaningful responses to climate change will be pulling in the same direction as those concerned about peak oil’s potential impact, so never say never…

Bottom line: At present we expect world oil supply to peak during this decade, all the talk about the shale boom and new frontiers and improved technology and “peak demand” notwithstanding. We lean toward a peak of world oil production within the next five years, with a very high level of confidence of a peak before 2030 (which would be 10-20 years later than we first expected). If we’re wrong and world oil production keeps growing past 2030, at that time you can email us or snail-mail us a copy of this essay as it will redeemable for the beer of your choice.

————————————————–

Our evolving approach to the ongoing transition from fossil fuels towards renewable energy resources has been appearing in the Peak Oil Review for more than a year. During our first decade, we concentrated on the geology of oil and gas production. We now are following geopolitics (wars, insurgencies, and political upheavals), the concerns about climate change, the global economy, and new developments which may bring non-polluting sources of energy or limit the demand for fossil fuels (such as electric cars). All of these have iterative impacts on trends in world oil production and consumption.

We will continue to follow the fundamentals of the oil, natural gas, coal, and electricity markets as these are and will remain the drivers of our civilization for many years. We hope that this change will give our readers a better sense of how the transition away from fossil fuels to other sources of energy is going.

Quotes of the Week

“The blistering growth rate of US shale was already running on fumes at the start of the year, before the coronavirus spread around the world. Drillers were struggling at $50 WTI. With prices so far below that level at this point, the wheels are coming off the shale complex. ‘When and if global oil markets stabilize, investors should remain deeply skeptical of a shale-sector turnaround, given the industry’s financially feeble performance over the past decade. Cautious investors would be wise to view shale-focused companies as high-risk enterprises characterized by disappointing performance, weak financial fundamentals, and an essentially speculative business model.’”

IEEFA analysts concluded in a new report.

“With Brent in the $25 per barrel range, roughly 10 percent of global supply is uneconomic.”

Nick Cunningham, oilprice.com

“In such an environment, it is as possible for Brent prices to briefly go to $10 per barrel as it was back in 1986 or 1998.”

JBC Energy, in a note

Graphic of the Week

| Contents 1. Energy prices and production 2. Geopolitical instability 3. Climate change 4. The global economy and trade wars 5. Briefs 1. Energy prices and production The global economy and the oil industry continue to be dominated by the coronavirus pandemic. With more countries, especially the economically advanced oil-consuming ones, going into some form of lockdown every day, the world’s oil consumption is now believed to be down by nearly 25 percent. Oil prices declined for a fifth straight week from collapsing demand due to the virus and increasing supply from producers vying for market share. Brent crude settled down 8 percent for the week at $24.93 a barrel, and US crude settled down more than 3 percent during the week at $21.51 a barrel. US oil futures now have fallen 65 percent this year and are on pace for the most painful quarter since at least 1990. As oil crashes, it’s easy to overlook an even more dismal reality for some oil producers. Actual cargoes are changing hands at large and widening discounts to the global benchmarks. These discounts mean that in the physical market, some crude transactions are trading at $15, $10, and even as little as $8 a barrel. In at least one market, crude prices have gone negative – meaning that producers have to pay to have the oil hauled away. The world may soon run out of space to store its surplus oil as Saudi Arabia prepares to increase its fossil fuel production even as global demand continues to fall. Storage levels have climbed to about three-quarters full since the January shutdown of refineries in China’s industrial heartlands to stem the coronavirus. Product storage saturation at refineries is set to occur over the next few weeks. At that point, oil product surplus will become a crude surplus, and its unprecedented velocity will create similar logistical crude storage constraints. This is the point at which crude prices will fall below cash costs to reflect producers having to shut-in production. Canada may be days away from running out of storage for its domestic oil production, and the rest of the world likely will follow suit, forcing producers to shut in production. The oil industry’s meltdown already is accelerating as drillers shut down scores of rigs across the US in response to low crude prices and expanding supply gluts. Oil companies idled 40 rigs last week, twice the pace of last week’s reduction and the steepest contraction since April 2015, according to Baker Hughes. More than half the shutdowns occurred in the Permian Basin, a sign for an industry that survived the last market crash in large part by retreating to that region because of its resilience to weak pricing. Halliburton, the No. 3 overall service provider, is planning for almost two-thirds of all rigs on the continent to shut down by the fourth quarter. |

2. Geopolitical instability

Baghdad is proposing that all foreign oil firms operating in the country cut their budgets by 30 percent on the condition that crude production levels do not suffer. Iraq is struggling with oil around $25 a barrel, and its oil ministry is having trouble paying the international oil companies that develop and operate major oil fields in the southern part of the country. Foreign firms who develop Iraqi oil fields do so under service contracts and are being paid a fixed fee in US dollars for their oil production plus reimbursement for their costs. In essence, the IOCs working in the country are being asked to take a 30 percent cut in their cost reimbursements while maintaining the same level of production. If the foreign companies pull out of the country, Iraq’s oil output would be seriously hurt.

The US once again extended a waiver allowing Iraq to import Iranian electricity and natural gas despite the sanctions on doing business with Tehran. The purpose of this waiver, which the United States is renewing, is to meet the immediate energy needs of the Iraqi people. The extension is for 30 days, the shortest extension yet for Iraq, and will be the last extension issued, AFP reported Thursday. State Department officials did not respond to requests for additional information.

Saudi Arabia wants to flood Europe with cheap oil to take away part of its former ally Russia’s European market. The Kingdom is intent on unleashing growing crude oil volumes, aiming to significantly boost its crude oil exports to a record-breaking more than 10 million b/d. However, it looks like demand for the ultra-cheap Saudi crude doesn’t exist after all. Many refiners in Europe and the US are refusing to take more Saudi crude being offered at cut-rate prices.

The Saudi Arabian Oil Co. said earlier this month it was cutting most of its prices and planned to boost its production by 2.5 million barrels a day next month. Some refiners in Europe, including supermajor Shell, are set to take less crude from the Kingdom in April.

The US is urging the Saudis to back off its oil price war, with Secretary of State Pompeo calling Crown Prince bin Salman on Tuesday. The official Saudi Press Agency said the two “reviewed exerted efforts to maintain stability in the global energy markets.” The call came ahead of a G20 leaders’ videoconference that the Saudi King hosted on Wednesday to discuss the response to the coronavirus outbreak.

Aramco has yet to prove that it can follow through on its plans to pump an unprecedented 12 million b/d of crude — almost 1 million b/d higher than it has ever produced before. Aramco has only recently recovered from last September’s missile attack on its Abqaiq crude processing facility, so that pumping at that volume will be a severe test of state oil company’s capabilities and infrastructure. Over the weekend, the Saudis shot down a Houthi missile aimed at Riyadh.

Saudi Arabia could suffer a budget deficit of as much as $61 billion this year under the double blow of the coronavirus pandemic and the global oil glut. This would represent almost 8 percent of the Kingdom’s GDP.

Venezuela is looking to shut in some of its operational oil wells as oil buyers prove increasingly hard to find when worldwide demand is plunging. Earlier this year, Venezuela managed to achieve a slight increase in its crude oil output, but the pandemic cut crude production to 464,000 b/d last week.

The government has started shutting down gasoline stations across the country as a shortage of gasoline has prompted rationing. The government will leave only a few stations open managed by the army. These, however, will only service medical, food transport, and utility vehicles.

The US government indicted President Maduro and more than a dozen other top Venezuelan officials on charges of “narco-terrorism,” the latest escalation of the Trump administration’s pressure campaign aimed at ousting the socialist leader. The State Department offered a reward of up to $15 million for information leading to the arrest and conviction of Maduro.

Venezuela confirmed its first infections by the coronavirus. The health ministry says that 46 medical centers are “prepared” to receive COVID-19 patients. However, local physicians say the claim was false. It is widely known that hospitals have no blood pressure monitors, syringes, or reagents to diagnose coronavirus infections.

In Libya, black markets flourish, and civilians are resorting to desperate measures as the impact of Libya’s ongoing oil blockade diminishes fuel supplies. Beyond the main coastal towns and cities, there’s no fuel for Libyan civilians now. Most fuel, both in western and eastern Libya, is being sent to the frontlines. These are the crucial frontlines in the ongoing battle for Libya’s capital between forces loyal to the UN-installed, Tripoli-based Government of National Accord and the forces loyal to General Haftar.

3. Climate change

How the pandemic will affect efforts to control climate change over the long term is still very much an open question. Air pollution in some of Europe’s major cities has dropped dramatically since governments ordered citizens to stay home. Readings from the Copernicus Sentinel-5P satellite show a significant decline in the concentrations of nitrogen dioxide over Rome, Madrid, and Paris, the first cities in Europe to implement strict quarantine measures.

Indians breathed easier last week as lockdowns ordered to combat the spread of the virus in India’s megacities kept cars off the road and factories closed, improving air quality and letting people see blue skies instead of heavy gray smog. But this is only a short-term phenomenon. As shut-ins are lifted, factories and transportation return to normal, the polluted skies will quickly return.

In the days leading up to the signing of the $2.2 trillion relief bill, lobbyists descended on Washington in an attempt to squeeze as much as possible out of the US Treasury. Some industries, including agriculture and aviation, got major boosts; others, notably coal and clean energy, were left disappointed.

There was hope among climate activists in the US that the federal stimulus to address Covid-19 might be the moment to heal the economy and transition to clean energy. However, whatever they’d envisioned, the $2 trillion bill wasn’t it. The push for clean energy drew fierce opposition from Senate Majority Leader McConnell and conservative critics, who accused Democrats of trying to exploit the urgent need for coronavirus relief to foist an environmental agenda on a wounded country.

Along with temporarily reducing greenhouse gas emissions and forcing climate activists to rethink how to sustain a movement built on street protests, the global response to the coronavirus pandemic is also disrupting climate science. Many research missions and conferences scheduled for the next few months have been canceled, while the work of scientists already in the field has been complicated by travel restrictions, quarantines and other efforts to protect field researchers from the pandemic. The field research season in Greenland and the Arctic, which normally starts ramping up this time of year, has been particularly hard hit.

The massive Denman Glacier in East Antarctica is creeping down a slope and plunging deep into the sea. New research finds that the newly submerged ice is creating a feedback process that could eventually dump trillions of tons of ice into the ocean with the potential to raise sea levels by nearly five feet over the long term.

The world’s wind power capacity grew by almost a fifth in 2019 after a year of record growth for offshore windfarms and a boom in onshore projects in the US and China. The Global Wind Energy Council found that wind power capacity grew by 60.4 gigawatts, or 19%, compared with 2018. The growth was powered by a record year for offshore wind, which grew by 6.1GW to make up a tenth of new windfarm installations for the first time.

4. The global economy and trade wars

The world’s economy is contracting so rapidly that it will be many months before the full extent of the damage can be assessed. With around one-third of the world’s population quarantined, working from home, or unable to participate in regular economic activity, the global GDP is will soon undergo an unprecedented drop. As the coronavirus spreads from the current “hotspots,” the situation is likely to get steadily worse for the next few weeks, months, possibly years. Past epidemics eventually afflicted as much as 70 percent of the world’s population, suggesting that our current economic problems may continue for quite some time.

We know that oil consumption, a rough measure of economic activity, is likely down by nearly 25 million b/d or 25 percent. Some authorities are saying that, if the situation does not improve soon, a depression rivaling that of 90 years ago may be at hand. So far, most of the impact has been felt in major industrial regions such as in China, Europe, parts of Asia, and the US. In some countries, all economic activity except for essentials as food, medicine, and infrastructure have been shut down. Other significant economically important nations — India, Japan, Argentina and in the Middle East — are shutting down or taking actions to limit the damage they have seen in the countries already coping with the virus.

As the pandemic spreads, it is becoming apparent that more havoc will be wrought beyond closing businesses and confining people to their homes. The complex logistic trails that source parts from all over the world will play an essential role in reestablishing economies after the coronavirus has played out.

China is telling us that it already has suppressed the coronavirus and, for the time being, is forbidding entrance to the country by people coming from abroad. While Beijing is saying that its people can go back to work, there still appear to be severe travel restrictions in some regions. These include recent certifications that a person seeking to travel is virus-free before being allowed on a train or plane, and some are complaining that these are hard to get.

Even though China lifted the quarantine on Hubei province and will lift it on Wuhan city on April 8th, it will be some time before business returns to normal.

American firms in China are increasingly pessimistic about how quickly they can rebound. Only 22 percent of the companies surveyed by the American Chamber of Commerce in China last week say they’re back to normal, while a quarter expects to be there by the end of April. Another 22 percent say they expect further delays through the summer. These resumption rates are well below official claims that over 90 percent of manufacturing companies and more than 60 percent of services firms are back at work.

Even if Beijing succeeds in keeping the coronavirus under control in-country, its export business and transportation links are in shambles. With its significant customers such as the US and Europe largely shut down and the global shipping industry, including oil tankers and container ships in a mess, it will likely be months before world trade pattern return to “normal” and even then, some trade patterns seem likely to change permanently.

India’s prime minister ordered all 1.3 billion people in the country to stay inside their homes for three weeks starting last Wednesday — the most significant and most severe action undertaken anywhere to stop the spread of the coronavirus. “There will be a total ban on coming out of your homes,” the prime minister, Narendra Modi, announced on television Tuesday night, giving Indians less than four hours’ notice before the order took effect at 12:01 a.m.

“Every state, every district, every lane, every village will be under lockdown,” Mr. Modi said. The breadth and depth of such a challenge are staggering in a country where hundreds of millions of citizens are impoverished, and countless millions live in packed urban areas with poor sanitation and weak public health care.

5. The Briefs (date of the article in the Peak Oil News is in parentheses)

Oil industry hammered: It is no exaggeration to say the oil industry faces its gravest crisis of the past 100 years. As western economies go into hibernation, hoping to snuff out the first wave of coronavirus through lockdowns and isolation, the industry is facing up to the fact that fuel demand is going to fall faster than ever before. For an industry long aware that a 1-2 percent swing in the balance of supply and demand can be the difference between prices soaring or collapsing, the extent of the fall in consumption is hard to process. As Europe and North America hunker down, the latest estimates suggest 10 to 25 percent of global consumption could vanish in the coming few months. (3/24)

The world’s biggest oil and gas firms should break an industry taboo and consider cutting dividends, rather than taking on any more debt to maintain payouts as they weather the fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, investors say. The top five so-called oil majors have avoided reducing dividends for years to keep investors sweet and added a combined $25 billion to debt levels in 2019 to maintain capital spending while giving back billions to shareholders. The strategy was designed to maintain the appeal of oil company stocks as investors came under increased pressure from climate activists to ditch the shares and help the world move faster toward meeting carbon emissions targets. Now, this strategy is at risk. (3/26)

A new OPEC+ deal to balance oil markets might be possible if other countries join in, Kirill Dmitriev, head of Russia’s sovereign wealth fund said, adding that countries should also cooperate in cushioning the economic fallout from coronavirus. Dmitriev was one of Russia’s top negotiators in the production cut a deal with OPEC. The current agreement expires on March 31st. (3/27)

The Middle East is pushing ahead with most of its top oil and gas projects planned as higher-cost regions, including the US, Canada, and the Arctic, suffer the brunt of cancellations due to the latest crash in oil prices. (3/24)

Nigeria, Africa’s largest oil producer, has discounted deeply its crude and aims to pump as much as it can, trying to retain customers in the unprecedented demand plunge. (3/28)

Nigeria’s double bind: This month, the price of oil tumbled from $50+ to less than $30 a barrel. It’s a double whammy for oil-dependent countries. With oil accounting for 96 percent of Nigeria’s exports and over 75 percent of its revenue, and with oil prices in a downward spiral, Nigeria is utterly vulnerable, unable to cope with significant pandemics. Thankfully, coronavirus hasn’t yet swamped Nigeria. But if COVID-19 hits this country in its full force, the truth is that Nigeria won’t be able to cope with the ensuing health crisis, economic emergency, and social calamity. (3/26)

In Canada, the Covid-19 virus and the ongoing oil price war have created such a massive global supply surplus that Western Canada’s oil production will need to be cut from April by some 11 percent, or 440,000 b/d, Rystad Energy estimates, as the country is days away from running out of available storage capacity. (3/24)

The US oil rig count declined by 40 last week to 624, the steepest drop in five years, according to Baker Hughes. More than half the shutdowns occurred in the Permian Basin. Gas rigs also declined by four to 102 active units. (3/28)

The shale revolution that made the US the world’s biggest oil and gas producer and offered the prospect of energy self-sufficiency has run out of steam, as drillers slash spending and production in response to the coronavirus-led collapse of crude demand. US oil output, now at a record high of 13 million b/d, will begin falling steeply in the second half of this year and could drop 2.5 million by the end of 2021. Even a modest further oil price drop could cut US production back by almost 4m b/d, fully reversing three years of increases. (3/26)

Storage nearly full: The glut of US oil is growing so fast that at least one pipeline owner is concerned wily traders may try to stow away crude on its network until prices improve. Plains All American Pipeline requires customers to prove they have a buyer or place to offload crude they’re shipping through the company’s pipes. The idea is to prevent anyone from using Plains’ network for parking oil while waiting for higher prices. (3/26)

Jet fuel demand dead: The coronavirus pandemic has ravaged the passenger travel industry. The International Air Transport Association (IATA), which represents airlines, said it has written to the heads of governments of 18 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including India, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines for emergency support for carriers. IATA estimates the pandemic will cost the global industry $252 billion in lost revenues this year. (3/26)

US airlines have already eliminated the vast majority of international flying and have announced plans to cut back domestic flying by as much as 40 percent. Travelers are staying home at even higher rates. The TSA reported that passenger flow at its checkpoints was down more than 80 percent Sunday from the same day a year earlier. Airline executives, pilot-union leaders, and federal transportation officials said they increasingly view as inevitable further sharp reductions from already-decimated schedules in passenger flights. (3/24)

Jet fuel storage crunch: A collapse in air travel due to the coronavirus pandemic has brought with it a plunge in fuel demand and the threat of a shortage of places to keep unwanted supplies. The picture looks sure to worsen in the coming weeks and months unless oil refineries take the drastic action of their own to cut output. Flight cancellations are destroying demand for the roughly 7 million b/d market, with some traders speculating consumption could have already dropped by as much as 50 percent. (3/23)

Negative oil prices! In an obscure corner of the American physical oil market, crude prices have turned negative — producers are paying consumers to take away the black stuff. The first oil stream to turn upside down was Wyoming Asphalt Sour, a dense oil used mostly to produce paving bitumen. Mercuria Energy Group, a trading house, bid negative 19 cents per barrel in mid-March for the crude, effectively asking producers to pay for the luxury of getting rid of their output. (3/28)

Fill the SPR? The Trump administration will continue to urge Congress to appropriate $3 billion to fill the Strategic Petroleum Reserve with US crudes after lawmakers removed the plan from a coronavirus relief package. (3/27)

Should leasing lockdown? The Trump administration is pushing ahead with drilling lease sales as oil prices plummet and amid calls from conservation groups and others to suspend business as usual during the coronavirus outbreak. The Bureau of Land Management held lease sales in Wyoming, Montana, Nevada, and Colorado on Monday, selling oil rights on parcels of public land covering hundreds of thousands of acres. But taxpayer groups argue the sales come at an inopportune time, as oil prices fall to roughly $23 a barrel, risking generating little income for the treasury. (3/26)

US retail gasoline prices dropped below $2 a gallon for the first time since March 2016, before President Trump was elected. The average pump price fell to $1.99 per gallon Friday, retail tracker GasBuddy said. On March 1st, prices were at $2.41. (3/28)

Gasoline futures in New York fell as much as 13 percent to $0.50 a gallon, the lowest level since the current contract started trading in 2005. All of which means Americans – on average – can expect gas prices at the pump to plunge below $2/gallon very soon. (3/24)

99-cent gasoline! It happened at one in Kentucky. Then at another one in Tennessee. And then at four more in Oklahoma. A handful of fueling stations across the country are bringing back something that hasn’t been seen since the days of big hair and brick phones — 99-cent gasoline. Nationwide, the price at the gas pump has plummeted as normally car-crazy Americans stay off the roads and, in their homes, to avoid spreading the novel coronavirus, which has already killed more than 19,000 people around the world. (3/27)

The wave of oil industry spending cuts continues, with the majors now announcing significant reductions to spending as oil remains stuck in the $20s. Royal Dutch Shell said on Monday that it would cut spending by 20 percent, or about $5 billion, and also suspend its share buyback plan. French oil giant Total SA and Norway’s Equinor announced similar moves. ExxonMobil and Chevron have suggested they, too, would be axing their budgets. Goldman Sachs estimates that Chevron needs $50 per barrel to cover spending and its dividend. ExxonMobil, on the other hand, requires something like $70. The majors are relatively more insulated from the downturn than small and medium-sized shale drillers because they have downstream refining and petrochemical assets that have typically performed somewhat better than upstream units when prices fall. (3/24)

Oil refiners across the US are being forced to throttle back operations amid a historic plunge in gasoline demand and prices. Orders to shelter at home are grounding flights and keeping drivers off the roads, crushing fuel demand, and profit margins. Companies delayed planned maintenance to stem the outbreak, adding to the fuel glut. (3/25)

US factories received fewer orders for business equipment than forecast in February, just before the coronavirus-related demand shock that will likely lead a massive pullback in corporate investment. Core capital goods orders, which exclude aircraft and military hardware, fell 0.8 percent after a revised 1 percent advance in January. (3/26)

Electric Reliability Council of Texas wholesale spot power prices have jumped higher than the five-year March average high as parts of the state hit 90-degree weather more than a month early. Hub prices across the ERCOT footprint have climbed between 22 percent and 39 percent week on week as temperatures started to spike March 23rd across the state, in contrast to the 50s and 60s just a few days earlier. (3/28)

Guilty: PG&E, a utility that supplies electricity and natural gas to 16 million people, or about one in 20 Americans, admitted that its failure to maintain its equipment was criminally negligent and caused the deaths of more than 80 people. Evidence showed that the company’s maintenance problems resulted from decisions made by many people over many years. The San Francisco utility disclosed that it would plead guilty to an indictment in Butte County, where 85 people died during the Camp Fire. The company has agreed to pay a $3.48 million penalty, the statutory maximum. (3/24)

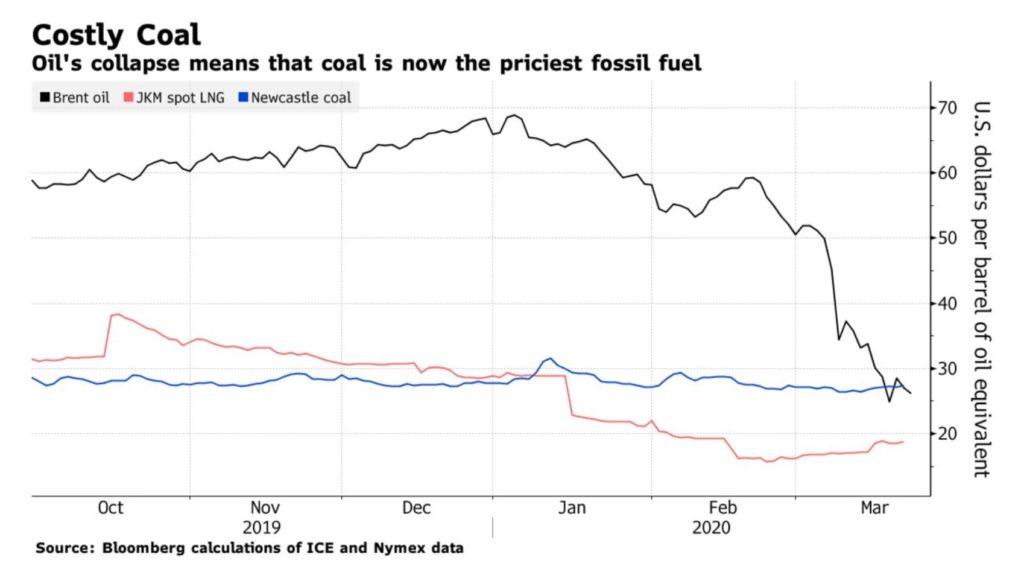

Coal, the dirtiest and usually the cheapest option for energy is now the world’s most expensive fossil fuel. Oil’s epic collapse over the past month means the global crude benchmark is currently priced below the most widely traded coal contract on an energy-equivalent basis. (3/24)

Coal grew during 2019: The world’s net capacity additions of coal-fired power generation rose by 34.2 GW during 2019 for the first time since 2015, due to a surge in the Chinese coal fleet, a new report from environmental organizations shows. As much as 64 percent of the newly commissioned coal capacity was in China, another 12 percent came from India, and the remaining 24 percent was mainly in Asian countries, including Malaysia, Indonesia, and Pakistan. (3/27)

Electric plane: NASA has released a series of concept images of the all-electric X-57 Maxwell airplane, showcasing aspects of its final Mod IV configuration during different flight modes. (3/28)

In the US, the official count of coronavirus infections sits at about 140,000 cases, but a chronic shortage of tests means only a fraction of the people infected is being counted. So how can we know how many Americans actually might have the disease? A Reuters/Ipsos nationwide poll conducted in the past several days could offer a hint of the possible numbers. Some 2.3 percent of Americans surveyed said they’ve been diagnosed with the coronavirus, a percentage that could translate to several million people. Of course, it’s impossible to know if the answers are a result of misinformed self-diagnoses, untested professional diagnoses, or test-confirmed infections. (3/27)

The cruise-ship industry, mainly Carnival-owned Princess ships, was at the center of the early spread of the virus into the United States. Behind the scenes, cruise industry executives lobbied Trump and other officials to allow ships to continue traveling to and from the country, with the industry’s handling of the crisis among top administration officials. (3/27)

Tanker and container-ship crews trapped: An estimated 150,000 crew members with expired work contracts have been forced into continued labor aboard commercial ships worldwide to meet the demands of governments that have closed their borders and yet still want fuel, food, and supplies. (3/26)

Shipping shocked: The global economy’s most abrupt and consequential shock in at least a generation is unfolding at ports, and other hubs of international commerce as the US and Europe struggle to contain the coronavirus pandemic. The Great Recession, the 11 September attacks, the 1973 oil embargo — none of these current crises constricted trade flows as quickly and as sharply as the Covid-19 disease has. (3/26)

National food hoarding? It’s not just grocery shoppers who are hoarding pantry staples. Some governments—so far, only a handful—are moving to secure domestic food supplies during the coronavirus pandemic. Kazakhstan, one of the world’s biggest shippers of wheat flour, banned exports of that product along with others, including carrots, sugar, and potatoes. Vietnam temporarily suspended new rice export contracts. Serbia has stopped the flow of its sunflower oil and other goods, while Russia is leaving the door open to shipment bans and said it’s assessing the situation weekly. (3/26)

European governments weighing the economic damage of a mass shutdown against the risk of spreading the new coronavirus were initially hesitant to impose stringent lockdowns and border closures. But as the pace of infections and deaths accelerated, Europe has broadly coalesced around a strategy: Freeze now and worry later about the bill. (3/26)

The eurozone is sinking into the most significant economic crisis in its history as measures to contain the coronavirus pandemic bring much of the business world to a standstill. IHS Markit’s gauge of private-sector activity plunged to the lowest since the index was started — and the currency bloc was formed — more than two decades ago. (3/24)

Seasonal swings? As Covid-19 circles the globe, the most severe outbreaks so far clustered in areas of cold, dry seasonal weather, according to four independent research groups in the US, Australia, and China that analyzed how temperature and humidity affect the coronavirus that causes the disease. If their conclusions are borne out, sweltering summer months ahead might offer a lull in new cases across the densely populated temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. In turn, that lull could be followed by a rebound next fall when cooler weather returns. (3/24)

Russia is beginning what Vladimir Putin called a “non-working week” to try to slow the spread of the coronavirus. The government is urging people to stay at home, though mixed messaging has left many Russians confused. Officials now hint the new restrictions could be extended beyond 5 April, depending on the health situation. The number of Russians infected with Covid-19 passed 1,000 on Friday, with most cases detected in Moscow. (3/28)

Russia’s official data showing a low rate of infections caused by the novel coronavirus underestimate the real scale of the disease outbreak in the country, a senior Russian official has warned Vladimir Putin. Addressing the Russian president on Tuesday during a televised meeting with senior officials about the pandemic, Sergei Sobyanin, a former presidential chief of staff and Moscow’s mayor since 2010, said that many coronavirus patients were not tested. (3/25)

Russia’s economy needs about a trillion rubles, or roughly $12.7 billion a month over the next few months to emerge stable from the coronavirus pandemic and the oil price crash, the chairman of a business organization told TASS.

Russia’s debt load is much smaller than that of other economies, so recovery should be relatively smooth. Russia’s debt to GDP ratio is, in fact, among the lowest in the world. (3/26)

Italy’s catastrophe: The number of coronavirus cases in Italy is probably ten times higher than the official tally, the head of the agency collating the data said on Tuesday as the government readied new measures to force people to stay at home. Italy has seen more fatalities than any other country, with the latest figures showing that 6,077 people have died from the infection in barely a month, while the number of confirmed cases has hit 64,000. However, testing for the disease has often been limited to people seeking hospital care, meaning that thousands of infections have certainly gone undetected. (3/25)

In Israel: After years of political paralysis, political parties are finally putting aside their differences to form a government against the backdrop of a daunting COVID-19 epidemic. But the unity government is the product of necessity and not genuine political resolution, so the day the current health emergency ends are the day their disputes will resurface again. (3/28)

India’s economy was sputtering even before its leader announced the world’s most extensive coronavirus lockdown. Now the state-ordered paralysis of virtually all commerce in the country has put millions of people out of work and left many families struggling to eat. (3/26)

Pyongyang has secretly asked for international help to increase coronavirus testing in North Korea as the pandemic threatens to cripple its fragile healthcare system. After reports of the outbreak emerged from Wuhan in January, North Korea immediately shut its borders, and its officials have not reported any confirmed cases of coronavirus. (3/27)

South Africa, with only 709 confirmed coronavirus cases as of 25 March, may be lagging a few weeks behind the outbreaks now unfolding in Europe and North America. But when the pandemic does eventually hit the country, it will hit hard. With high rates of people living with HIV or tuberculosis, much of South Africa’s population is immunosuppressed and thus believed to be at risk. (3/27)

Most leaders in Latin America reacted to the arrival of the coronavirus in the region with speed and severity: Borders were shut. Flights were halted. Soldiers roamed deserted streets enforcing quarantines, and medical professionals braced for an onslaught of patients by building field hospitals. But the presidents of Brazil and Mexico, who govern more than half of Latin America’s population, have remained strikingly dismissive. They’ve scoffed at calls to shut down business and sharply limit public transportation, calling such measures far more devastating to people’s welfare than the virus. (3/26)

Unusual emissions: A chemical plant near Pensacola (FL), owned by Houston-based Ascend Performance Materials, emitted 33,046 metric tons of nitrous oxide in 2018. That’s equal to the annual greenhouse gas emissions of 2.1 million automobiles. The plant makes adipic acid, one of two main ingredients for nylon 6.6, a robust and durable plastic used in everything from stockings to carpeting, seat belts, and airbags. The plant’s nitrous oxide emissions are more colloquially known as “laughing gas.” From a climate perspective, the plant’s emissions are no joke. (3/25)

Climate locusts: As giant swarms of locusts spread across East Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and the Middle East, devouring crops that feed millions of people, some scientists say global warming is contributing to the proliferation of the destructive insects. The largest locust swarms in more than 50 years have left subsistence farmers helpless to protect their fields and will spread misery throughout the region. (3/24)